The first post of my blog on the AI industry was on March 10, 2023. It covered Georgi Gerganov’s incredible “hack” with Llama.cpp, and the simultaneous collapse of Silicon Valley Bank. Almost three years later, finance and AI are completely intertwined, which motivated this finance-heavy post. It is also an opportunity to revisit my predictions for 2025 posted at the end of 2024, as well as many anecdotes from my career in finance. This post can be read as three distinct parts as I gradually zoom out from products, to market, to society. On some platforms, each sub-section will be published independently.

The post is very US-centric because, even though I do use Chinese models extensively and I consider myself knowledgeable about Chinese products, I don’t feel familiar enough with Chinese-style capitalism and Chinese society to provide a commentary as thorough as for the West on the industrial strategy.

I’ll try to refrain from using the word “bubble” for as long as possible in this post. But regardless of the term we use to describe the current market environment, OpenAI is at the heart of it. They secured preemption rights for virtually all technologies that could be necessary to their scaling, and everyone currently speculates on their ability to convince a large base of consumers to pay for their services. But they can’t achieve this without a strong product strategy and near-perfect execution. So before analyzing the financial wizardry around the company, let’s discuss AI products, and OpenAI's in particular.

Consumer-centric

In May 2025, I described OpenAI's then-recent shift in strategy, highlighting that they seemingly turned their attention away from regulators and prospective investors (this war had been fought and won) and started to focus on users. I commented that, despite bumps in the road, like GPT-4o’s “Glazegate”, it may be a winning strategy.

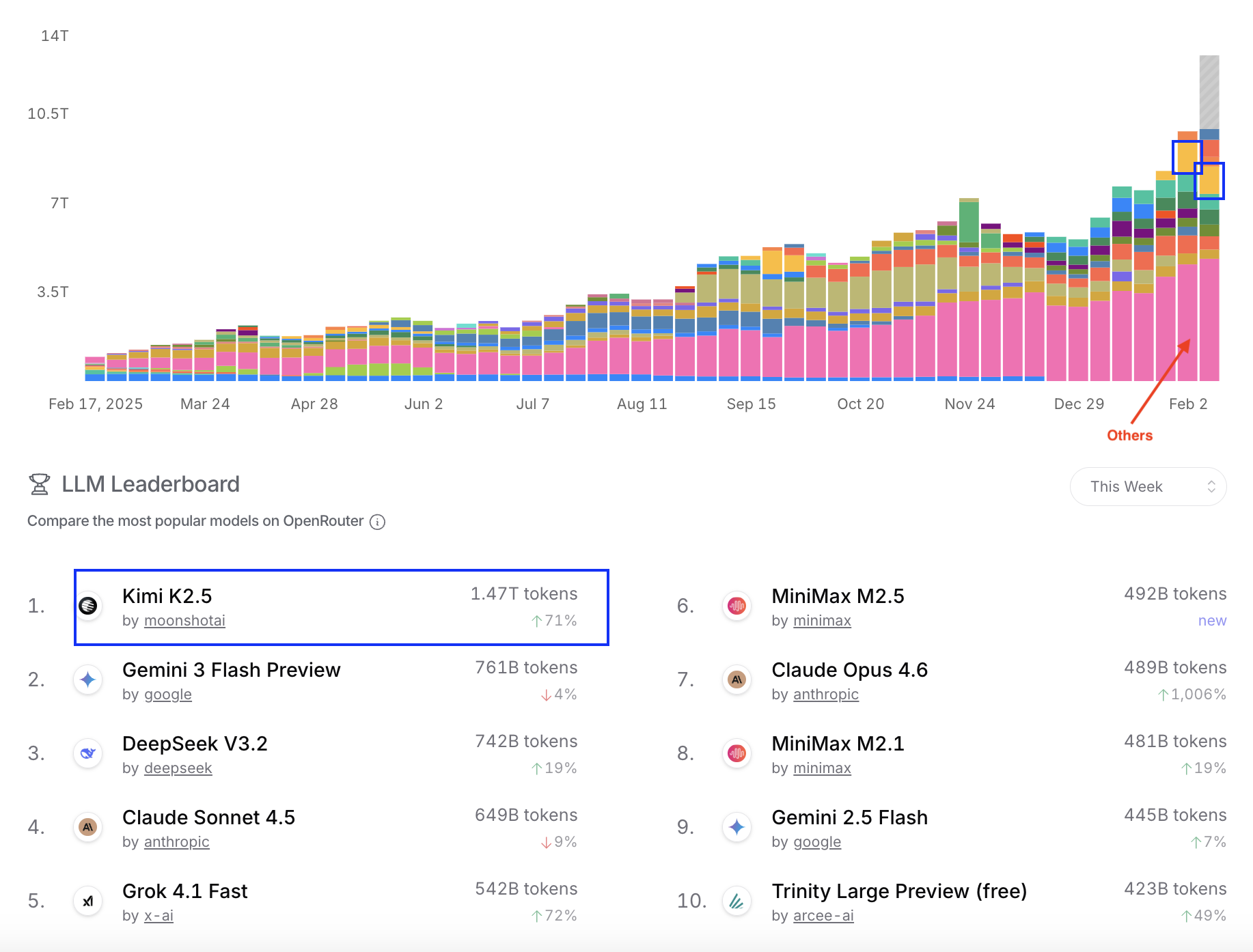

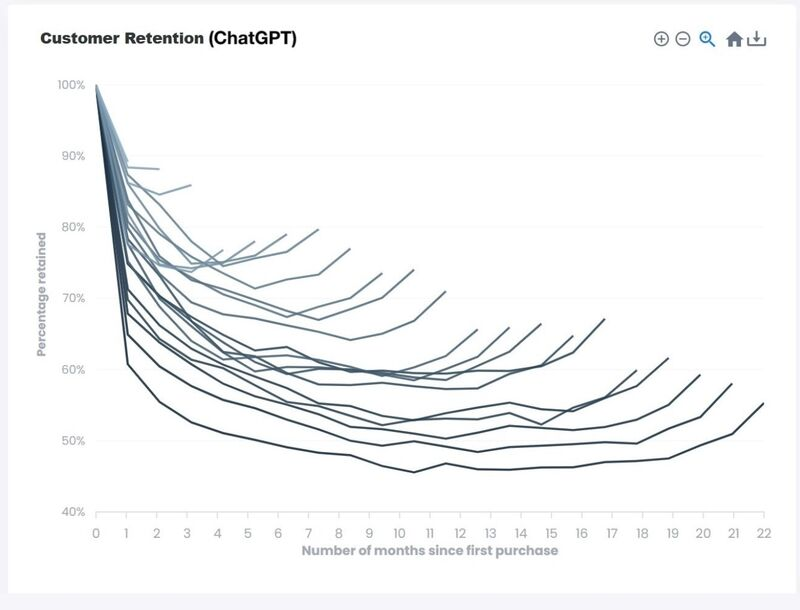

You shouldn’t look for proof that OpenAI's strategy has worked in 2025 in industry benchmarks. Artificially topping these flawed rankings has become a secondary concern for top-tier labs in 2025. The best evidence that OpenAI's strategy is working is the cohort graph that leaked (purportedly?) in September 2025. What this graph shows is user churn. The X-axis is the time since sign-up. The Y-axis is the retention rate over time. The longer the curve, the earlier the sign-up date. Curves go down because some users sign up, try chatGPT a few times, and stop using the product. ChatGPT’s curve shapes are surprising because of their asymptotic level: even for the lowest curve, a 50% retention is incredibly high. More recent cohorts do not drop as much as the others in the initial period, demonstrating a better retention. To be clear, anything above 85% at that scale is absolutely astonishing. Improving retention levels point to an improving product. This is further confirmed by yet another oddity of the ChatGPT curves: starting 5 or 6 months before August-September 2025, all curves have started going upwards, meaning that users that had dropped off are returning! This is not just a seasonality effect, e.g. students returning to school and using ChatGPT again to cheat on their homework. The "smile" indicates that the product is improving; the point I made in May is vindicated.

OpenAI continues to roll out their aggressive consumer-centric strategy by throwing ideas at the wall to see what sticks. Not all releases are equally mind-blowing but there are legitimately innovative - and potentially disruptive - products coming out of the firehose. Most people look at Sora 2 as a flop 3-4 months after its release, but I think it was a very good preview of what future AI-native products could look like.

Sora 2

The video modality has been on a strong dynamic in 2025. For this reason, Sora 2 was not in itself a major surprise. There are very good models for this modality, including Google’s Veo, Kling, ByteDance's Seedance or even open-weights ones like Alibaba’s Wan family or, in 2026, LTX-2.

Sora 2 stood out for two reasons: the model’s understanding of the context and … an actual product, completely separate from ChatGPT. OpenAI launched an app that immediately went viral as moderation was initially very loose - likely to facilitate engagement and virality. Google applied the same strategy upon release of Nano Banana Pro... and Seedance 2.0 (February 2026) was demoed with virtually no moderation regarding IP.

I can’t say that I feel very enthusiastic about short-form video content generated to maximize virality, but I must acknowledge that the product was well thought out: the feature called cameo lets users embed their own images in a video but they can also embed images of third parties who authorized it. The rights-granting process was built-in from the outset, which demonstrates OpenAI's attention to details. This detail, in fact, is the avenue for monetization for rights holders. I understand that the rights-handling platform underpins the deal with Disney, whereby Disney will invest $1bn in OpenAI (and receive warrants) and OpenAI will be allowed to use the Disney intellectual property in its image/video models.

Because of this specific feature, I think that Sora 2 is innovative and potentially disruptive. I’m convinced that it could have been a massive consumer success… provided they had enough compute to serve this product at scale. This platform needs critical mass to benefit from network effects. I can see how OpenAI could quickly pivot Sora 2 to B2B but it seems unlikely that they give up the consumer market easily.

B2B vs. B2C

Over the last couple of years, I’ve changed my mind on B2B vs. B2C. It’s been clear forever that Anthropic (or Cohere or Mistral) were positioning themselves better to address the B2B segment, which I interpreted as a worrying sign for OpenAI. However, when I listen to normal business people talking about AI, it is clear that ChatGPT is synonymous with LLMs in most people’s minds. And it’s very rare that they can name a competitor. That brand awareness is largely attributable to OpenAI's B2C strategy.

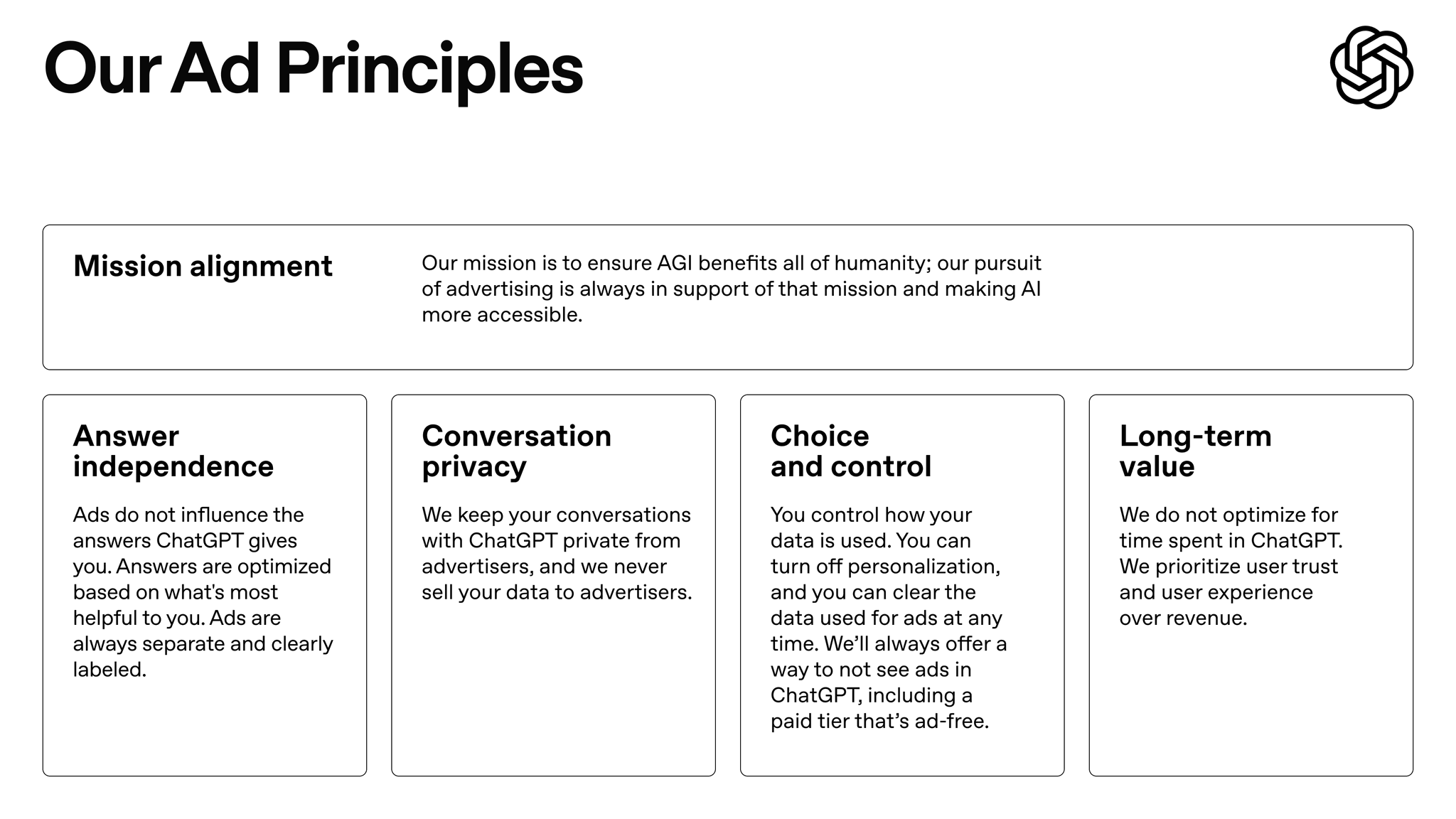

So while I still believe that B2B is the relevant path to profitability, I now think OpenAI is not wrong to push hard on the B2C segment. They act as if any compute bottleneck can be solved - see below - and, if that’s the case, Sora 2 could be a proof of concept for a product that adds enough value to justify a subscription. In addition, it gets users hooked, which opens the door to advertising revenues. It has long been suspected that OpenAI had a roadmap to add this revenue stream. Sam Altman alluded to it in early 2025. If you consider that only 5% of the users are paying a subscription(1), you understand how critical this monetization strategy could be to finance OpenAI's future capex. In January 2026, they finally made it official by announcing ads in ChatGPT, along with a number of principles they plan to adhere to.

Other consumer products, like Pulse (limited to Pro users as far as I know), shopping research, which Google is deploying as well, or the Atlas web browser could also leverage users’ usage data for monetization via ads.

The Atlas browser collects a ton of data, but monetization may not be the primary motivation. In this case, OpenAI is probably more interested in usage data to further train AI agents to use a browser. I was originally dismissive of network effects for generative AI but there definitely is a virtuous cycle when more users means more data, which in turn leads to a better product that attracts more users. When it comes to browser use, another immediate benefit of developing an effective agent is that the product can go around search engines API restrictions by using a browser directly. The key issue for Atlas is not that it can’t simulate a web search - it can -, but that the moderation layer will not even let users search topics that do not align with OpenAI's values.

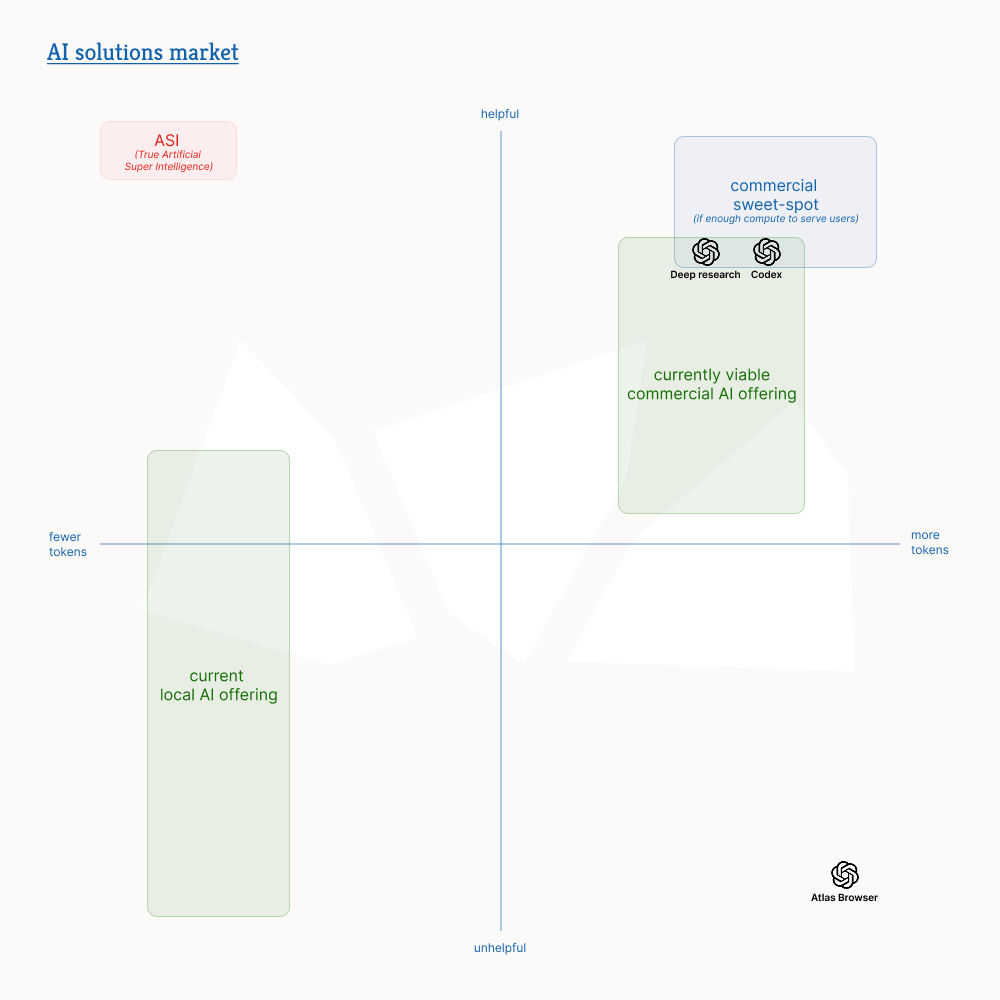

Magic quadrant

As we’ve seen with Sora 2 or Nano Banana Pro in the early days, loose guardrails generally mean that a product is perceived as more useful by users. And when there is a perceived usefulness, users are willing to pay. AI companies then try to strike the right balance between utility for users and legal risk for the company. Against this backdrop, the path to profitability for most AI companies implies (1) finding legitimate product-market fit (i.e. users find the product useful), and (2) driving usage up with a usage-based pricing. Usage, in this case, is always a function of a number of tokens. Usefulness leads to more tokens. However, something peculiar about AI right now is that the relationship between usefulness and tokens is bidirectional: with test-time scaling, more tokens typically mean more usefulness (even though Anthropic themselves acknowledge that it can lead to a hot mess).

Hence the idea of mapping the AI solution market along two axes: usefulness and number of tokens.

- For the reasons mentioned above, the sweet-spot for commercial solutions is the top-right corner. More tokens, more usefulness.

- Local AI solutions typically sit on the left (fewer tokens) due to hardware constraints on VRAM and inference speed, limiting their ability to handle massive contexts or agentic loops.

- True Artificial Super Intelligence will optimize resources, and therefore minimize the number of tokens while maximizing usefulness. It will be on the top-left corner.

- AI solutions that rely on social media algorithms to hook users and serve ads may not need to maximize usefulness to exist, or at least not usefulness to end-users who are not the clients in that case. The solutions may need to produce more tokens if ads are inserted in a conversation (more turns mean more ads) but it would only be a downstream effect of a specific product form (chatbots).

Code agents perfectly illustrate what happens in the top-right corner and Anthropic in particular applies this strategy by focusing on usefulness to sell more tokens. Claude Code with Opus 4.6 would be on the right of Codex in the above quadrant. Other agent companies use the same playbook: Cursor released its Composer model leveraging a network effect to accumulate usage data and train a good coding agent model internally. The Composer model is priced similarly to Google’s and OpenAI's respective state-of-the-art models. Cognition/Windsurf, another code agent business, has also developed its own coding agent model. In each case, simple tricks in harness or system prompt contribute to the production of more tokens.

In last year’s End-of-Year post, I shared my skepticism about agents. As far as coding agents are concerned, I must acknowledge that my assessment was wrong. Claude Code in particular has established itself as a major AI product, which could be useful beyond coding. Coding is somewhat easier than more general tasks because the cost of verification (the largest cost item of AI agents, which is often ignored) is low so the agent can retry many times. For that reason, I still believe that we are very far from general agents yet I must admit that “agents” is the area where I’ve moved the goalposts the most in 2025.

OpenAI's alternative, Codex, is also very strong and there are many competitive open-source solutions from independent start-ups. Competitive enough that Anthropic had to cut access to users using these tools with an API key associated with a Claude Max plan (tokens sold at a discount by Anthropic compared to the API). This decision was the origin of a mini controversy amongst vibe-coders even though Anthropic had every right to do so, and developers can still get Claude Opus 4.6 at official API rates. I don’t see Anthropic’s move as primarily motivated by revenue growth, but rather as a defensive move to prevent competitors from accumulating too much data on users usage too quickly through telemetry.

Red hot AI

Why is usefulness so critical in this analysis? Because utility for users is what justifies the price a company can charge. In fact it’s about marginal utility: if marginal utility decreases very quickly, i.e. if users quickly have enough and can’t take more, then the price one can charge is low(2). The marketing gimmick that intelligence will become too cheap to meter is preposterous: if it becomes that cheap, it means that no one can take more, which would raise enormous questions regarding start-ups' growth prospects.

The AI industry doesn’t seem mature enough to solve the marginal utility equation. The lack of transparency means that service providers can get away with exaggeration, misleading information or blatant lies. Purposely vague product definitions keep them off the hook if anything goes wrong. Yet clients are happy to play along because everyone must have an AI strategy these days; anything that could signal to their boards and investors that they will not be left behind.

It’s only a matter of time before users start asking themselves how much value they truly derive from any additional token. This question is more fundamental in AI than in most industries because the cost of inference is tied to context length. As the context window fills up with conversation history, tool calls, and follow-ups, the compute required to generate the next marginal token increases. If you have followed the reasoning so far, you see that if marginal utility decreases steeply, price is low but marginal COGS for model provider actually increases.

Understanding this scissors effect is essential to the debate around the current health of financial markets given “AI stock” accounts for a record proportion of the S&P 500 and have contributed the bulk of its recent returns. This level of concentration is considered unprecedented in modern market history. In 2025, AI has seemingly transformed financial markets into meme stocks trading platforms where any announcement of a soft commitment to work with OpenAI, either as a supplier or a client, justified multibillion increases in market cap. The term “Press Release Economy” was apparently coined by @tylermacro10 in 2025, and it was a fair description of the state of financial markets at the end of last year.

On four separate days over the past two months, the stock prices of Oracle, Nvidia, Advanced Micro Devices, and Broadcom soared after they disclosed OpenAI-related deals-adding a combined $630 billion to their market value in the first day of trading after the announcements. A broader rally in tech stocks followed each time, helping lift the U.S. stock market to record highs.

Wall Street Journal, October 20, 2025

Outside of hyperscalers built upon another business (Google, Meta, Amazon, Microsoft), hardly anything can support current valuations. No cash flows, no assets; merely non-binding contracts dependent on energy infrastructure that will take decades to build (see The Impossible Build-out).

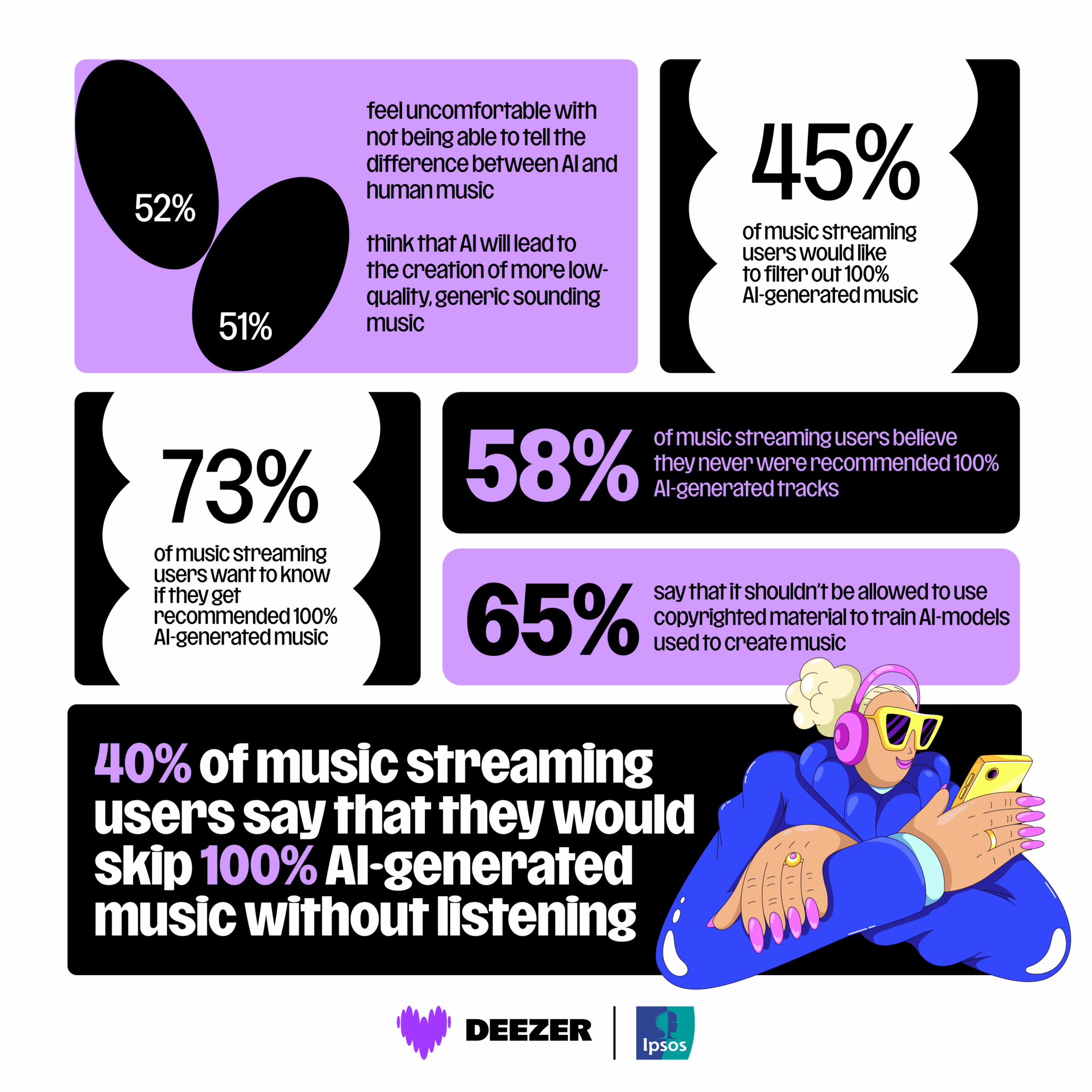

Notwithstanding the obvious shortcomings of most financial analyses around AI, I don’t consider all attempts to justify the current value of Nvidia (and by extension the entire AI semiconductor sector) stupid or uninteresting. The most sensible approach I’ve read focused on the value of intellectual property that is destroyed by generative AI: the rationale was that the cumulative value of those IP rights (trillions of dollars) was not actually destroyed but transferred to the most critical link of the generative AI value chain. I had touched on such transfer of value from content creators to engineers in the past but I never really thought about the implications in terms of market size for each category. As I said, I’m not sold on this theory but it is the only approach that holds water for me.

Intellectual property at risk: the AI music case study

One of the most overlooked AI technologies today is AI music. This corner of the ecosystem receives very little coverage, likely because the Majors are incredibly well organized to fend off any threats to their IP rights. They overcame the previous threat - piracy - and left a lasting impression of power. The best way to avoid messing with them seems to stay under the radar. Nonetheless, the tech is impressive - some claim that it matches the capabilities of human artists. This tech is already widely used in social media or even advertising. Suno, the best AI music platform to date, boasted $200m ARR in November 2025.

This threat will be harder to contain; this time is different. Record companies seem to have realized that the tide is shifting, and that they could be left high and dry if they don’t move fast. Anecdotal evidence of this realization is an AI-powered R&B artist named Xania Monet who signed a $3m-deal with the independent label Hallwood Media. At the end of 2025, Majors made strategic moves on music generation platforms, echoing the OpenAI/Disney partnership mentioned earlier (OpenAI is rumored to have an AI product on the roadmap by the way).

Universal (UMG) first signed partnerships with Udio (Suno’s competitor) and Stability AI while Warner (WMG) signed a partnership with Suno to create generative platforms to let users include officially-licensed human samples as part of their AI productions. The exact terms of the new platforms are yet to be disclosed by UMG but, following their partnership, Udio’s users are no longer able to download their creations. WMG stated in its press release that downloads would not be possible for free users and paid users would have limited access. In both cases, the lawsuits between the AI company and the Major were settled as part of the deal.

Absent more information, these partnerships look like attempts to lock down AI music by controlling the generation platforms. What can’t be protected through usual IP protection frameworks will be controlled through the platforms’ terms of service: if you breach the ToS, you lose access to all your content. This is exactly how OpenAI controls its platforms: your ChatGPT account can be deleted if you misuse Sora 2.

But what does it mean for artists if Majors control music generation platforms ? These initiatives funnel genAI revenues towards the Majors in exchange for making their portfolios available for sampling. In that instance, AI provides enormous leverage as virtually anyone can create tunes using samples regardless of technical skills. UMG and WMG are playing a volume game. But will artists receive anything when volumes increase? WMG said they could opt-in and receive a share of the revenue. UMG remained silent on the matter. Majors are known for taking advantage of artists in these types of situation (that’s why artists typically seek independence once they achieve fame) so it will be interesting to follow how this plays out.

From the Majors’ perspective, the strategic move is sensible, but it's far from obvious that it will be a winning bet. The issue is that the tech is not hard and it's virtually impossible to trace back the developer of a model or the data it was trained on. All you need is to not care about rights holders. There is no doubt that open source models originating from China will drop, and once the genie is out of the bottle, the Majors’ efforts could be pointless.

The Big Beautiful Bubble: BBB, investment grade

Here it is, “bubble”, I said it. I must be clear on my position on the AI industry: I believe it's going to be MASSIVE. The same magnitude as the Internet or the smartphone. But I feel that it lacks important fundamentals today.

I’ve been a first-hand witness of what a market lacking fundamentals looks like. I’ve seen it as an investment professional across various mini-bubbles, and I’ve illustrated it with NFT markets before that bubble popped. Most times, no one is to blame because, in reality, market valuations are always correct if/when there are enough market participants. It doesn’t mean that a valuation is good for you: as explained earlier, price depends on marginal utility for buyers, and you may not have any utility for a stock at a high valuation. However, during bubbles, speculative dynamics correspond to a financial utility of just holding an asset, assuming that someone else would pay a higher price later for that same asset and the gain you'll make will more than cover the cost of holding the asset. Such speculation can be totally healthy when that “someone else” has non-financial utility for the asset. It’s unhealthy when utility for them relies entirely on finding a 'greater fool' to sell it to.

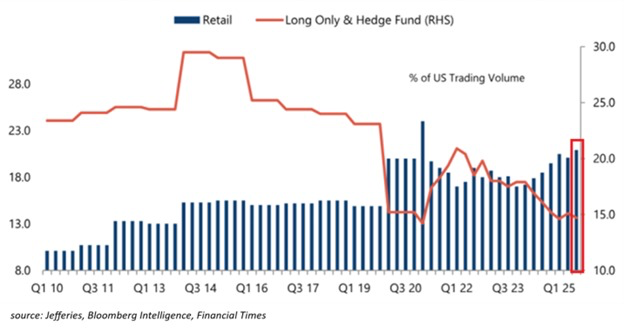

What’s particularly concerning today is that the flow increasingly comes from retail investors, while hedge funds and some institutional investors clearly have more prudent approaches. I could take a glass-half-full view and celebrate a flight-to-quality as many retail investors won’t be exposed to consumer discretionary spending when the rest of the economy collapses. But I can’t help thinking that it’s not a calculated bet: a lot of this volume is FOMO-driven and buyers have no idea about who could have non-financial utility for the bag they hold.

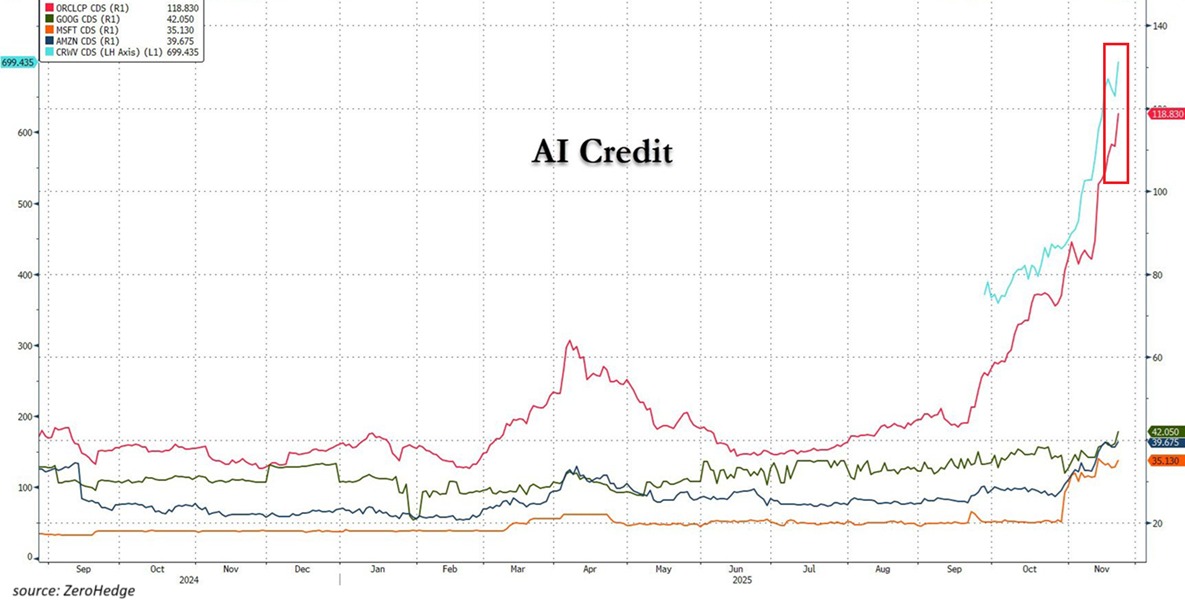

Not everyone is naive though: prices of Credit Default Swaps (CDS) of Oracle or Coreweave indicate that sophisticated investors either hedge their bets or directly bet against continued AI scaling. Concerns about these companies’ ability to service (or refinance) their debt in the future are legitimate, but their CDS also happen to be the best instruments to bet on a bubble-popping.

The bubble will eventually burst but there will always be survivors. The arms race isn’t about accumulating a war chest; it’s about climbing a hill as fast as possible, hoping to be safe when the tsunami hits.

No crying in the casino

The arms race is not unique to the US, it is very much a theme in China too. From an external perspective, the market for frontier AI looks much more competitive in China than it is in the US. This is because the playing field is more level amid hardware bottlenecks due to US trade restrictions. But also because of the very nature of Chinese markets: economic Darwinism is part of Chinese-style capitalism so no one will be blamed when the cleanup comes. In the US, when it happens, the greed of financial markets participants will be blamed. Irrespective of the economic doctrine, the end-state will be the same in the US and in China: an oligopoly with 2-3 behemoths.

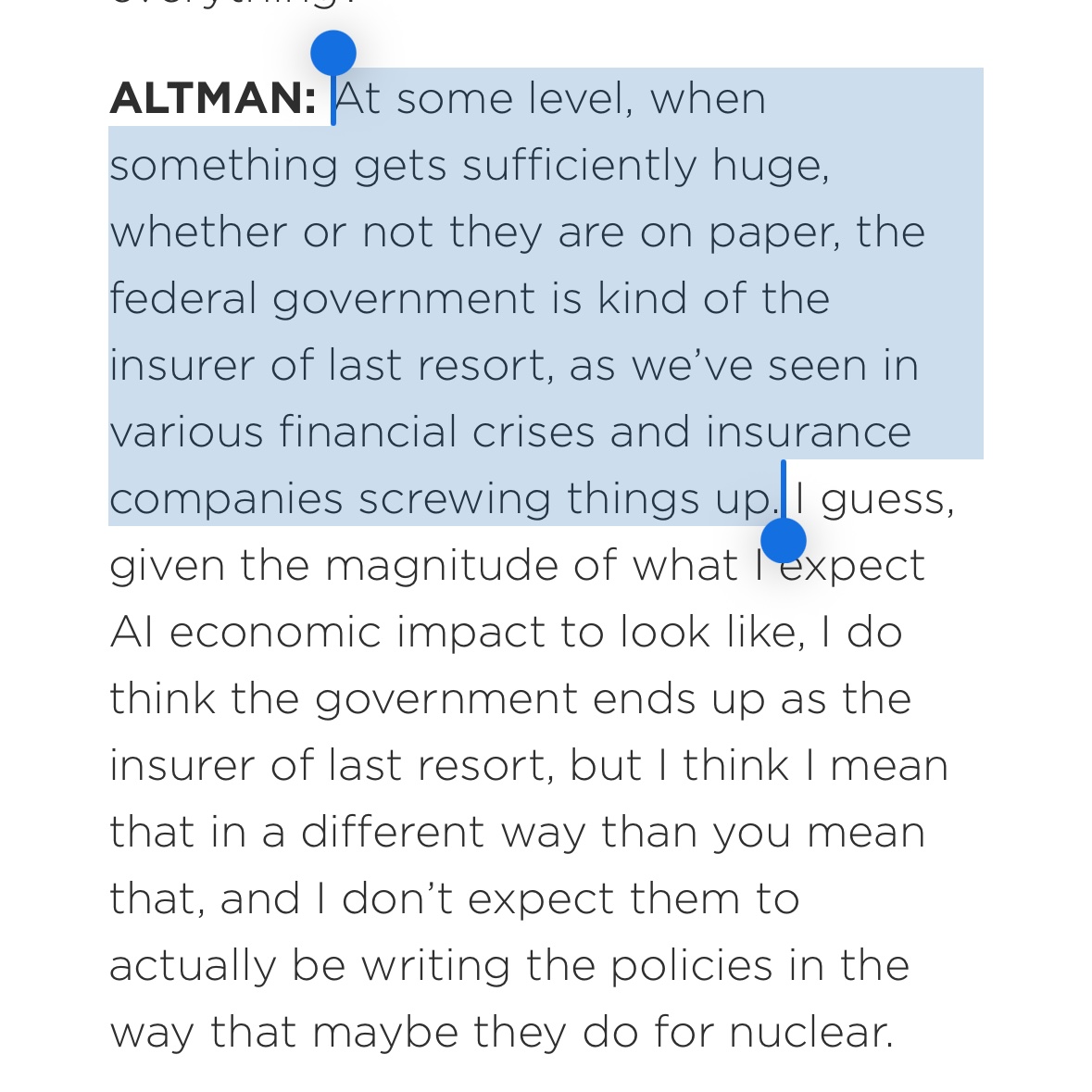

While the Americans seem to enjoy the gamble, the never-ending winning streak is an illusion. An illusion largely based on Memoranda of Understanding. If the music stops, these agreements are virtually worthless. No one will claim OpenAI's $1.4tn commitments ($1.8tn according to HSBC). These commitments are, at best, an option for OpenAI: if the current dynamics continue, OpenAI will have priority over compute and memory capacity. Based on a recent interview, Sam Altman sees it no differently: he said that they could resell capacity. By becoming a critical piece of the AI puzzle, OpenAI also positions itself as too big to fail… and they had to deny that it was precisely what they are aiming for.

Let’s ask the question differently: who isn’t big enough to survive a shakeout?

Collateral damage

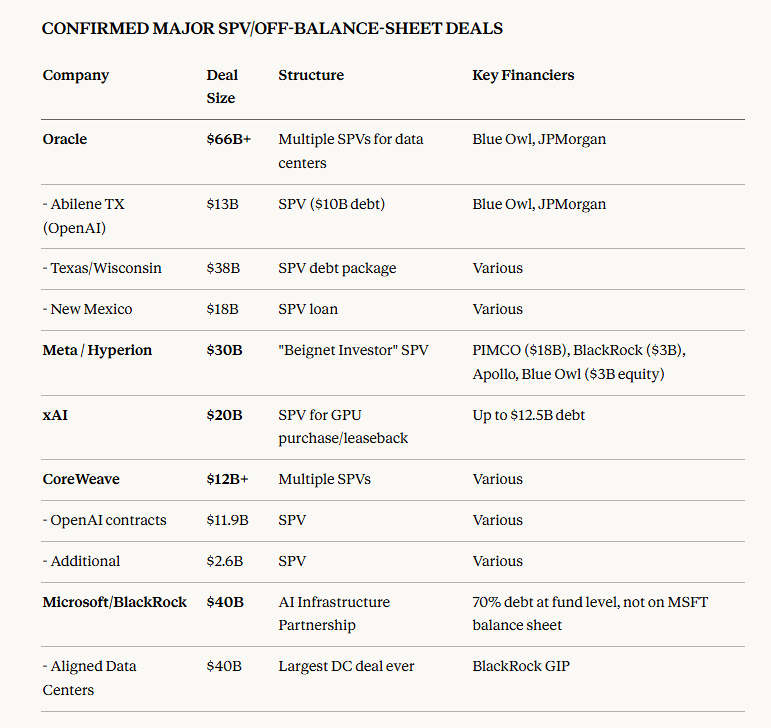

First and foremost, those who have been lured by financial wizards. One of the most concerning trends these days is how equity risk is engineered into investment grade investments. I personally don’t feel very strongly about people speculating on listed shares. I get it: they want the thrill, and if they get it right, potential upside is uncapped. I’m much less comfortable with debt being rated A. There is no upside and downside protections are questionable to say the least. If you don’t know these markets, you might think that a $20bn-financing issued by a Special Purpose Vehicle (SPV) with only very loose ties with an actual cash-flow generating business is the norm. It is really not; these jumbo deals are exceptional. And yet, several deals were announced in the last few months(3). If you don’t follow the financial news, look up what’s happening around Altice at the moment. Altice was one of the landmark jumbo deal(s) for my generation and the current developments were entirely predictable. There is no reason to believe that the AI jumbo deals will unfold differently.

Why do these financings happen? From a demand perspective (the borrowers), the primary motivation is that debt is one of the cheapest sources of financing. From the supply perspective (the underwriters), these large deals represent rare opportunities to generate a LOT of fees as fees are volume-based. This is a huge economic opportunity but only if they don’t get stuck with this paper, which means that they must be confident that they will resell it to institutional investors reasonably quickly. If they don’t, they’ll have to offer discounts to offload the debt, which will offset the underwriting fees on the P&L. I simplify the picture a bit but this is basically how it works. And this is where rating comes into play.

There seems to be genuine appetite for this type of debt (see point made above regarding a flight-to-quality given pretty terrible macro-economic perspectives). In February 2026, Alphabet (Google) issued a 100-year note, and the GBP tranche was 10 times oversubscribed! Don't believe that Google is special: Coreweave provides another anecdotal example of the appetite. Its DDTL 1.0 facility issued in July 2023 was priced at SOFR + 9.62% while the DDTL 3.0 facility two years later was priced at SOFR + 3.00%. Notwithstanding the general appetite for AI debt, the syndication market is limited to institutional investors and there is a lot of volume to absorb in a very short time frame. Banks need to tap investment-grade pockets because they are significantly deeper than for other categories. I won’t get into the details here as to why it’s the case, but the bottom-line is that large tranches of debt are more easily swallowed by the market when served with a A-sauce.

How do you get an investment-grade rating on a greenfield datacenter project? The obvious answer should be: you don’t. But the right answer is: you throw in a first-lien pledge on all assets (presumably valuable) plus hard volume commitments or guarantees from a credit-worthy institution. Now the devil is in the details: what assets are valuable? What commitments are hard? What counterparties are credit-worthy ?

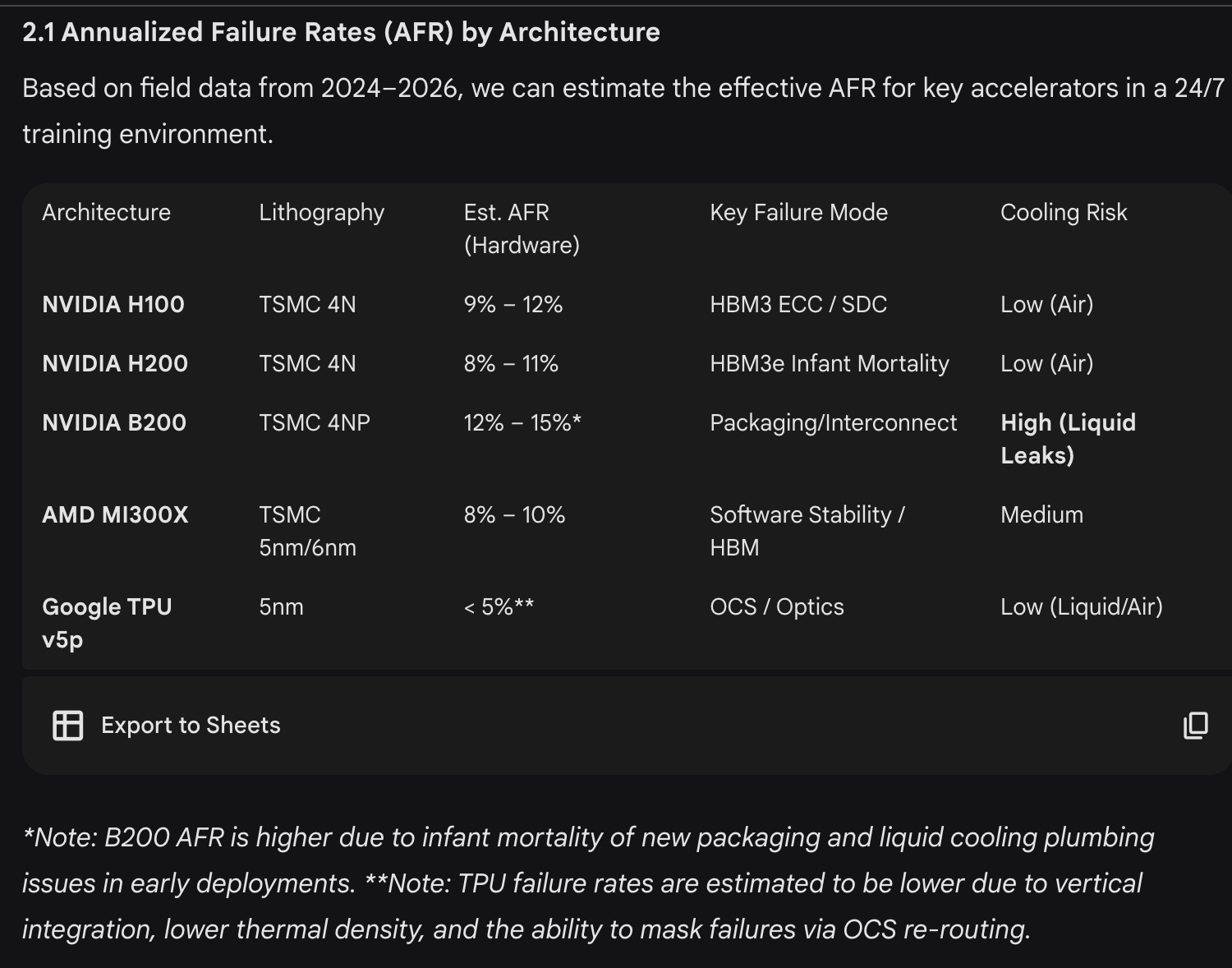

For AI datacenters, assets include the expensive chips (GPUs) that made Nvidia one of the most valuable companies in the world. Michael Burry - the Big Short guy - recently shared his concerns about the useful life of these devices, accusing firms of accounting fraud regarding asset depreciation. There are in fact two separate issues regarding depreciation: the accounting treatment and the actual lifecycle of GPUs. The latter should have a direct impact on the former but it does not seem like the market (nor the accountants) have all relevant information to bridge the two. In 2023, Coreweave’s $2.3bn financing was backed by GPUs and flew under the radar of most analysts. I did raise my eyebrows at the time. In retrospect, my concerns about lifecycles were not necessarily warranted. I expect that many people who now consider the useful life to be only three years will eventually draw the same conclusions as me.

There is an important caveat: everyone’s blind spot might be the failure rate of Nvidia GPUs. Nvidia’s best chips come with a 3-year guarantee and I gather that this guarantee is activated very often. There is no official data about failure rates for high-end Nvidia GPUs but META provided some stats for H100s in the LLama3 report (Table 5). By annualizing these stats, you quickly understand that failure rates are significantly higher than for traditional enterprise server components, which typically hover between 1% and 2%. Reports point to failure rates for H200s on parity with H100s, following a redesign of thermal management. B200s failure rates are understood to be higher. Given the lack of official information, I can't be certain that annual failure rates could be as high as 10%, but I’ve come to understand the reason why there is no market for second-hand datacenter GPUs: under 3 years old, no one wants to sell; beyond 3 years old, no one wants to buy even if the GPU could still work for many years.

The elephant in the room

Irrespective of the accounting treatment, the lack of secondary market is a very big deal for whoever has these GPUs as collateral for financial obligations. The assets can’t be repossessed by creditors: they have no resell value and know-how is critical to keep operating them. In fact, most times, the datacenter is not operated by the borrower but either by the party that provides the guarantee to the SPV, or by a third-party who gets significant business from the guarantor. In that case, guarantors have the upper hand: in the absence of a White Knight (i.e. a competitor of the guarantor that could take over the operations in short order), the creditors have no choice but to strike a deal with the guarantor because it is the operator that grants value to the assets. If you have ever been in a position to take over a defaulting business, it should be obvious to you that datacenter operators, with the financial backing of guarantors if they are different parties, will be ideally positioned to scoop the assets at incredible discounts. They literally hold the keys.

High switching costs and lack of depth in the operators landscape are not the only reasons why one should be concerned that downside protections have no teeth. In fact, the primary concern should be that the operator/guarantor itself defaults because it was not as credit-worthy as initially thought.

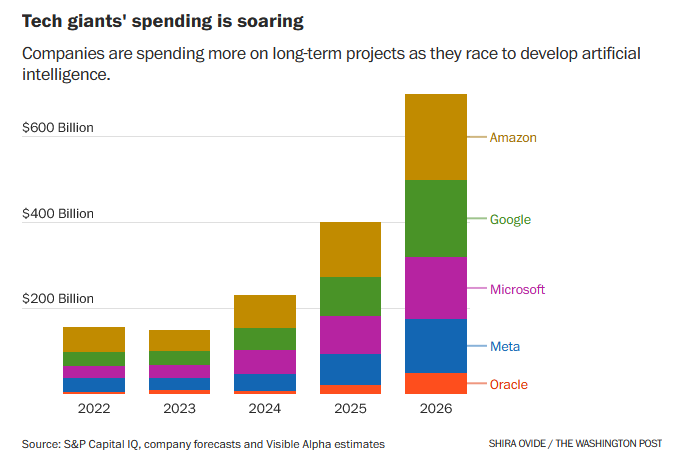

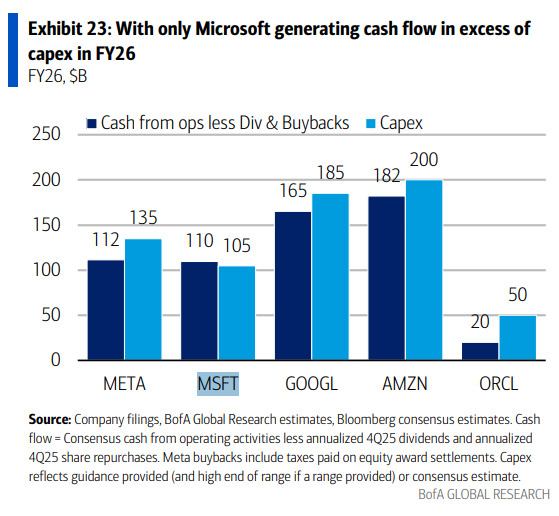

While the AI market is poised to be massive, many seem to overestimate the final market share of the horse they back. The AI opportunity is attractive at market level, but it sometimes feels like several companies lever the same future revenues. This is not a problem for the likes of Google, Meta, Microsoft (or Alibaba in China) which generate sufficient cashflows to spend tens of billions of dollars in capex each year(4). As explained above, these players could even be beneficiaries of over-investments in AI infrastructure if they can buy back their own datacenters for pennies on the dollar. It is much more problematic for neoclouds like Coreweave that depend on few clients (essentially 4 customers, one of which is OpenAI and the others resell to OpenAI) who in turn rely on third-party money to fill a funding gap.

Virtual money printer

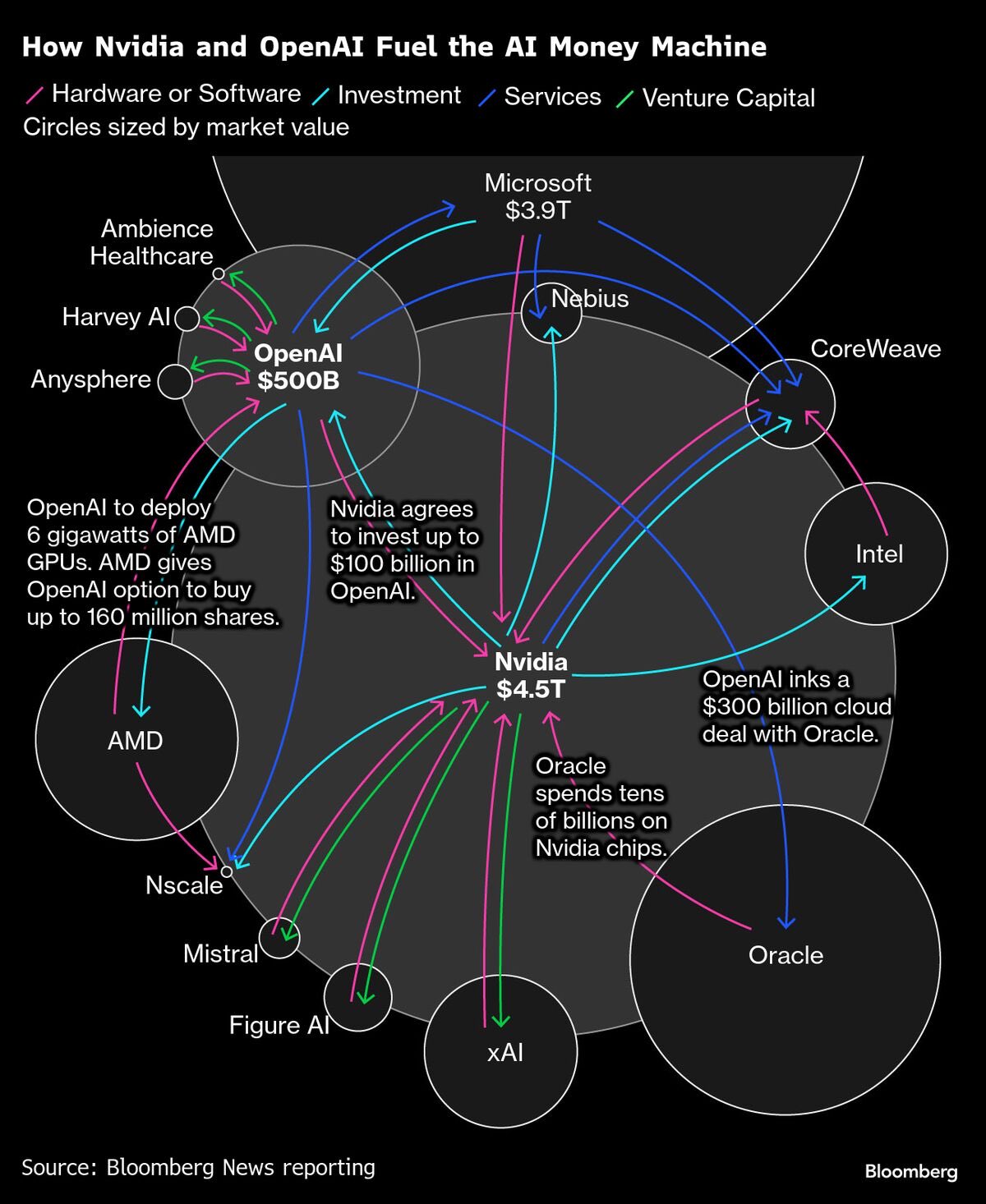

In Coreweave’s case, the third-party filling the gap is expected to be Nvidia, given how strong the ties are: Nvidia is the most important supplier, a key customer and a cornerstone shareholder. Coreweave exemplifies the incestuous deals that are common in the industry. There is nothing fundamentally wrong about Nvidia trying to reinvest the piles of cash it accumulates at the moment. They really are instrumental to these investments’ success, commercially or operationally. They can crystallize the equity upside in a reasonably liquid market after Coreweave’s IPO (the only possible liquidity event). I think it’s fair play.

When I first looked at these “strategic partnerships” in 2023, Microsoft was the figurehead with its multi-billion investment in OpenAI, securing both a revenue share AND the exclusive provision of cloud services. Even without liquidity on the OpenAI shares, Microsoft’s investment must be largely derisked in cash terms today. Exclusivity is no longer on the table as OpenAI has effectively outgrown what Microsoft considered a reasonable capacity to allocate to a single customer and, more generally, everything points to the fact that Microsoft does not want more exposure to the AI industry’s poster child. However, Microsoft did not entirely lose the appetite for such deals: in November they agreed to pour $5bn into Anthropic, alongside Nvidia ($10bn), in exchange for a pledge of $30 billion to run Claude’s workloads on Microsoft's cloud, powered by Nvidia’s latest chips.

In the Microsoft/OpenAI open-relationship, Microsoft isn’t the only one to shop around:

- In September, Nvidia announced that it would invest up to $100bn in OpenAI and supply GPUs.

- In November, OpenAI signed a $38bn deal to buy cloud services from AWS which could be [partially] financed by a $10bn investment by Amazon into OpenAI. This deal also corresponds to a diversification strategy for Amazon, which had most of their chips on Anthropic until this year. While the $10bn investment is still hypothetical, I believe it's very credible, both as a way to finance the $38bn cloud deal, but also as a sweetener for OpenAI because Amazon’s track record as Anthropic's model inference platform isn’t exactly stellar(5).

For both Nvidia and Amazon, it will be difficult to directly recoup the investment from cashflow from OpenAI unless the start-up raises additional funding. A potential IPO, rumored as early as 2026, would be critical not only for the ROI on the equity investment but also to help OpenAI fulfil its volume commitments towards its shareholder-clients.

Circular financing deals have been a key feature of the “Press Release Economy”. The list is long and each case is interesting on its own, but I want to highlight one in particular: in October 2025, OpenAI and AMD announced a strategic partnership whereby OpenAI would purchase 6GW worth of AMD GPUs over several years. In terms of potential revenue for AMD, this could represent up to $100bn. This deal stands out because, in this instance, AMD did not commit to investing in OpenAI to finance the purchase. In fact, neither OpenAI nor AMD could afford this deal based on their respective balance sheets. So OpenAI tried to be as innovative with financial engineering as it is with product development: OpenAI was offered warrants to purchase up to 160m AMD shares (up to 10% of equity) at one cent each, contingent upon a number of milestones being achieved by both OpenAI and the AMD stock.

The AMD stock immediately soared as a result of the announcement ($165 prior to the announcement and $205 as of February 12, 2026). If the stock rises to the $600 threshold defined in the agreement, OpenAI could see the value of the GPU deal fully offset by the warrants.

Read the excellent post on this deal by Dr. Ian Cutress

Can you be bullish on both Nvidia and OpenAI ?

As evidenced by the numerous compute deals closed in 2025, incredible capacity is being built up to power the next generation of AI models over the next 3-5 years. There are still a lot of question marks surrounding financing routes, and we’ll cover other obstacles to scaling in the rest of this post. But let’s take the optimistic view for now and jump straight to 2030 to ask what happens to this installed base once the industry has matured.

The GPUs' useful life is once again pivotal. Would another $3tn be needed to purchase the next generation of GPUs ? Or would chips still be usable for another 3-5 years?

If it’s the former, where would the money come from? Borrowing against the installed base does not seem like a credible option - hopefully lenders will have learnt by then that it really isn’t a good idea. A realistic scenario is that these GPUs could still work but the electricity cost makes it unprofitable compared to running newer chips. If millions of GPUs were to be disposed of, it also raises questions about the recycling of these very complex devices containing valuable parts and raw materials. Just like for EV batteries today, the capacity of recycling facilities may prove to be significantly short of expected volumes in a few years because building recycling plants costs billions and takes years. It’s a financial challenge as much as an environmental one. Managing GPUs' end-of-life may be the next AI infra play…

On the other hand, if chips can still be used for many years beyond 2030, what does it mean for Nvidia? Nvidia’s datacenter revenue would dry up substantially and the company would have to reinvent itself once again. In that scenario, the investment in OpenAI and all other AI startups could prove extremely important. I personally believe that it's plausible that the market quickly becomes smarter about compute strategies by switching a big part of the compute from GPUs to alternatives (e.g ASICS) or even CPUs. Being smarter should also help maximize utilization rates: if you are not an industry insider, the stupidly low utilization of current GPUs would shock you, in particular during training because the memory capacity is maxed out long before the compute capacity. Overall, being smarter should result in cheaper infrastructure and these strategies should also imply longer life-cycles. This scenario, where AI capex stalls or declines, is effectively the AI bull case, and by extension, the OpenAI bull case.

The OpenAI bull case

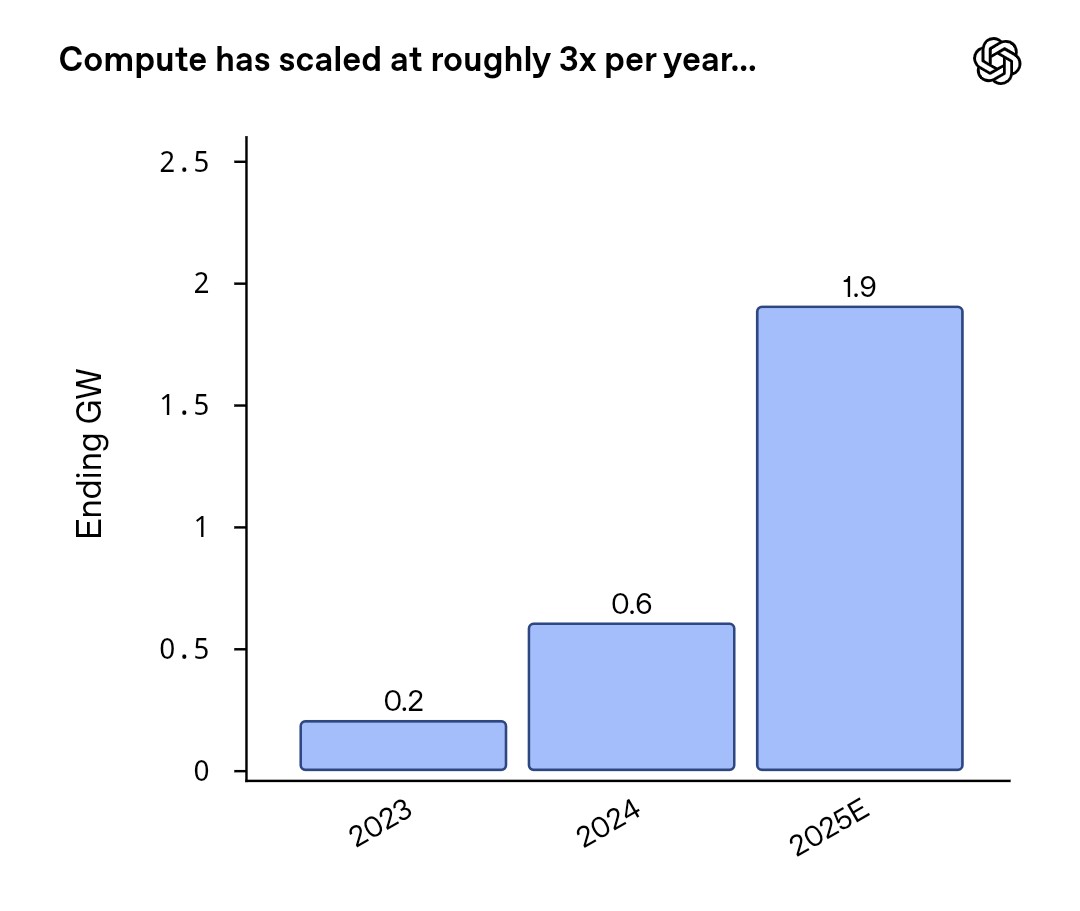

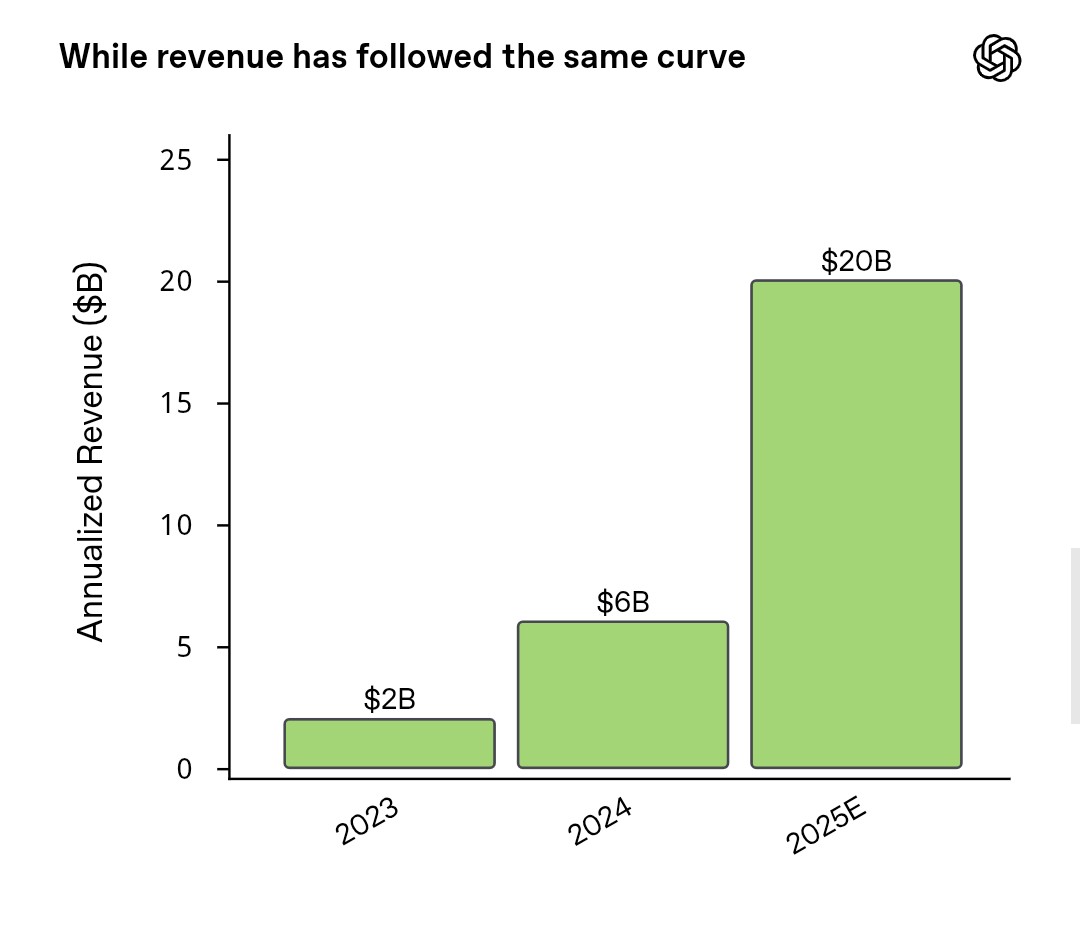

Let’s assume that OpenAI and the other prominent AI labs can fund the purchase of all the equipment. When we talked about OpenAI's product strategy, we heavily caveated the praises by saying that compute capacity needed to be front-loaded. The baseline hypothesis should be that labs with no other revenue streams than AI always overestimate the share of AI capex they can self-fund. The reason is that revenue can’t be generated without compute and, as per OpenAI's recent shareholder letter, annualized revenue (in $bn) is broadly equal to ten times the installed compute capacity (in GW).

But let’s be optimistic: compute will be financed by third-parties. Talking about “compute” capacity here is a massive oversimplification. In fact, all players in the AI value chain need to raise funds to purchase all the components of their future AI infrastructure, not only chips but memory, cables, and so on. And then they need to find skilled engineers to put these together. It would be only a mild hyperbole to claim that they have already reserved the volume of both components and skills that will be available globally until 2028 at least. Prices and salaries are surging as a result. This also concerns all metals involved in the AI value chain (the disaster in the Grasberg copper mine certainly didn’t help). This cycle even represents a bonanza for hotels located close to suppliers’ headquarters as everyone flies in for the "dog and pony show" in hopes of securing volumes. In 2026, consumers will be directly impacted because consumer tech businesses cannot compete with AI labs unless they hike prices significantly, and even then shortages are to be expected.

The optimistic case for AI is that shortages and price hikes for global tech components will not lead to disruptions for the AI supply chain. And so OpenAI and their peers can secure enough equipment and labor hours to build their infra as planned. This seems implausible today if you focus on production capacity for individual components but some of these components may not be strictly necessary after all. So, for the sake of the argument, let’s assume that big US labs WILL have over $3 trillion worth of latest-generation hardware (half of which for OpenAI alone) sitting in brand new datacenters and representing together 50-60GW of theoretical compute capacity. In February 2026, J.P.Morgan even pointed towards 120GW of visible demand, which would imply twice as much capex.

Pardon the ballpark figures but we are at a stage of the cycle where $10bn is a rounding error, and many of these “rounded” numbers are used as inputs by the AI commentariat (including myself) to calculate other numbers, which are in turn used to calculate other metrics, and so on. There is likely a lot of double-counting along the way so I recommend considering any figure as half-true, and deciding for yourself if you should halve it or double it to get a good enough interval.

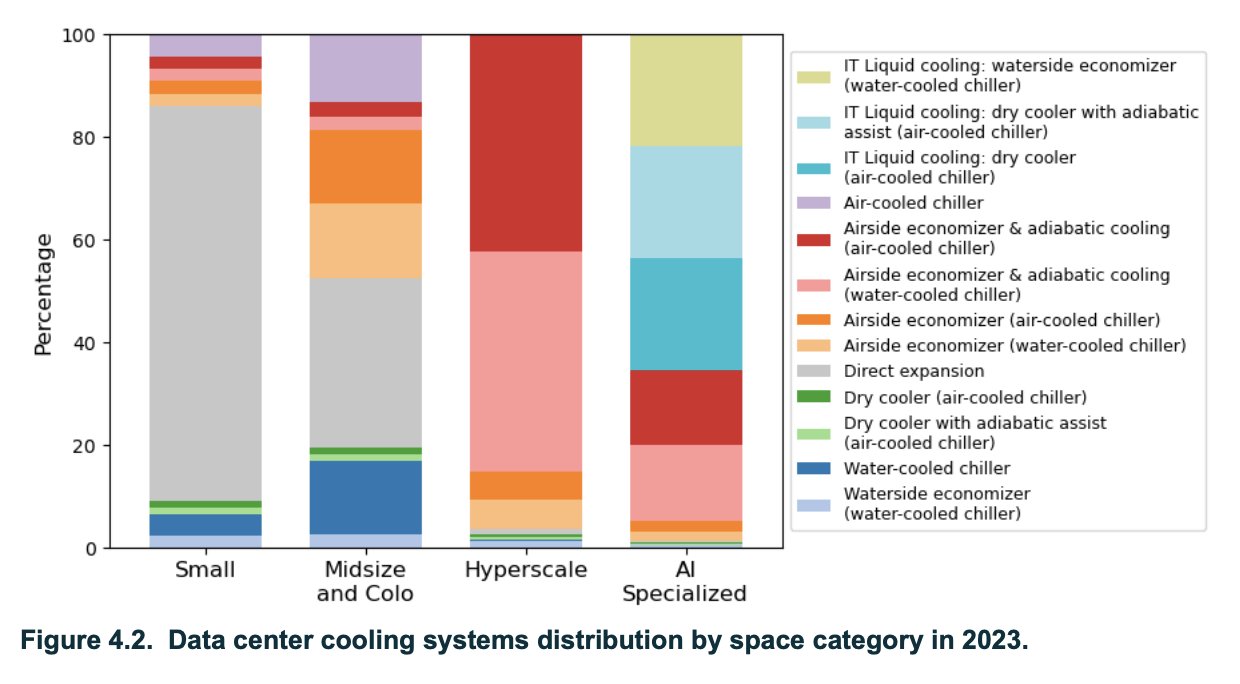

Gigawatts

If you’re not familiar with the datacenter industry, you probably wonder why everyone constantly measures compute capacity using gigawatts instead of operations per second - the infamous FLOPS metric used in AI regulations. Gigawatts are in fact a standard way of thinking about compute, considering the energy required to power the hardware 24/7. This includes the power draw of the chips but also the cooling system (see below) which is another big component. The number of effective floating point operations per second (FLOPS) doesn’t really matter in practice; the reality is almost counterintuitive: during training, when model FLOPS utilization is the lowest due to memory constraints, chips stay in high power state to ensure that, when the next batch of data does arrive, it can be processed immediately. Since the load at inference is more traffic-dependent, there may be more opportunities to drop to a lower power state (i.e unloading the model, not keeping the memory energized and ready) but it does not seem like many AI players have this luxury today. I could not find a robust source for the actual power draw of 1GW of compute capacity, but it seems like it could be north of 0.8GW, maybe north of 0.9GW, irrespective of how the models are used. They only need to be loaded.

We are talking about gigawatts here, so AI datacenters have to draw an enormous amount of power from… somewhere. For context, my MacStudio with an M2 Ultra chip uses just over 100W at full capacity. A GW is 10 million times that. If you gave 60 million households a 2023 MacStudio (or a 2025 MacStudio to 30 million households) and asked them to run local models 24/7 they would use just as much power as what the OpenAI/AMD deal represents(6). To put the US grid in perspective, the energy production capacity in the US is ~1.2 TW across the entire country, and only a fraction of that is productive over a year (under 50% in 2023 if I got my math right: ~1.2TW should translate to ~10,500 TWh over a year but only ~4,200 TWh were produced).

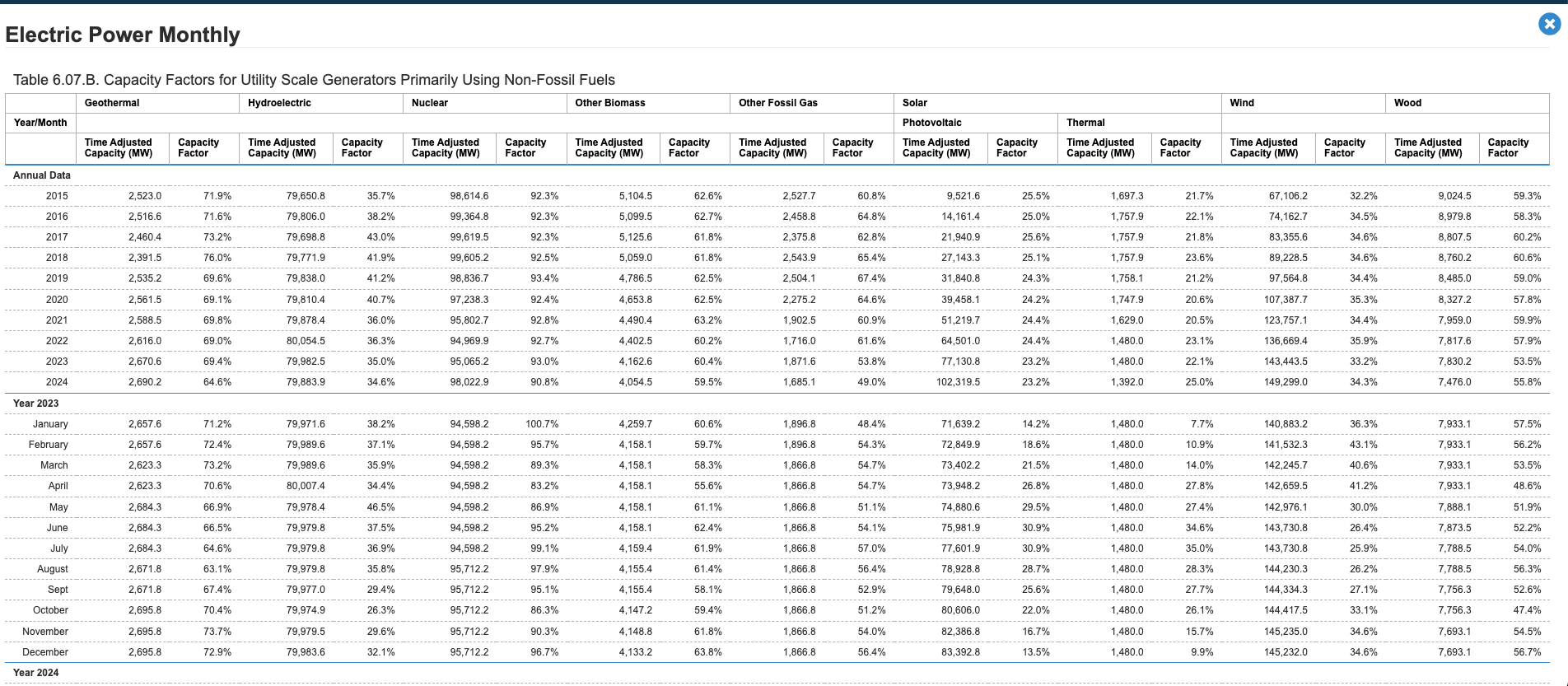

You might think: “hold on, everyone’s whining about AI’s power requirements, but it’s only 5% of today's total capacity (assuming 50-60GW added in the US by 2030), all we are talking about is adding another 5-10%”. I think it's important to put the AI energy demand in perspective but it should not be dismissed as insignificant in the grand scheme of things because adding 10% is no small feat when it comes to energy. The current capacity is already running close to its maximum effective utilization because some power sources simply cannot generate their full capacity 24/7 throughout the year (e.g solar or wind).

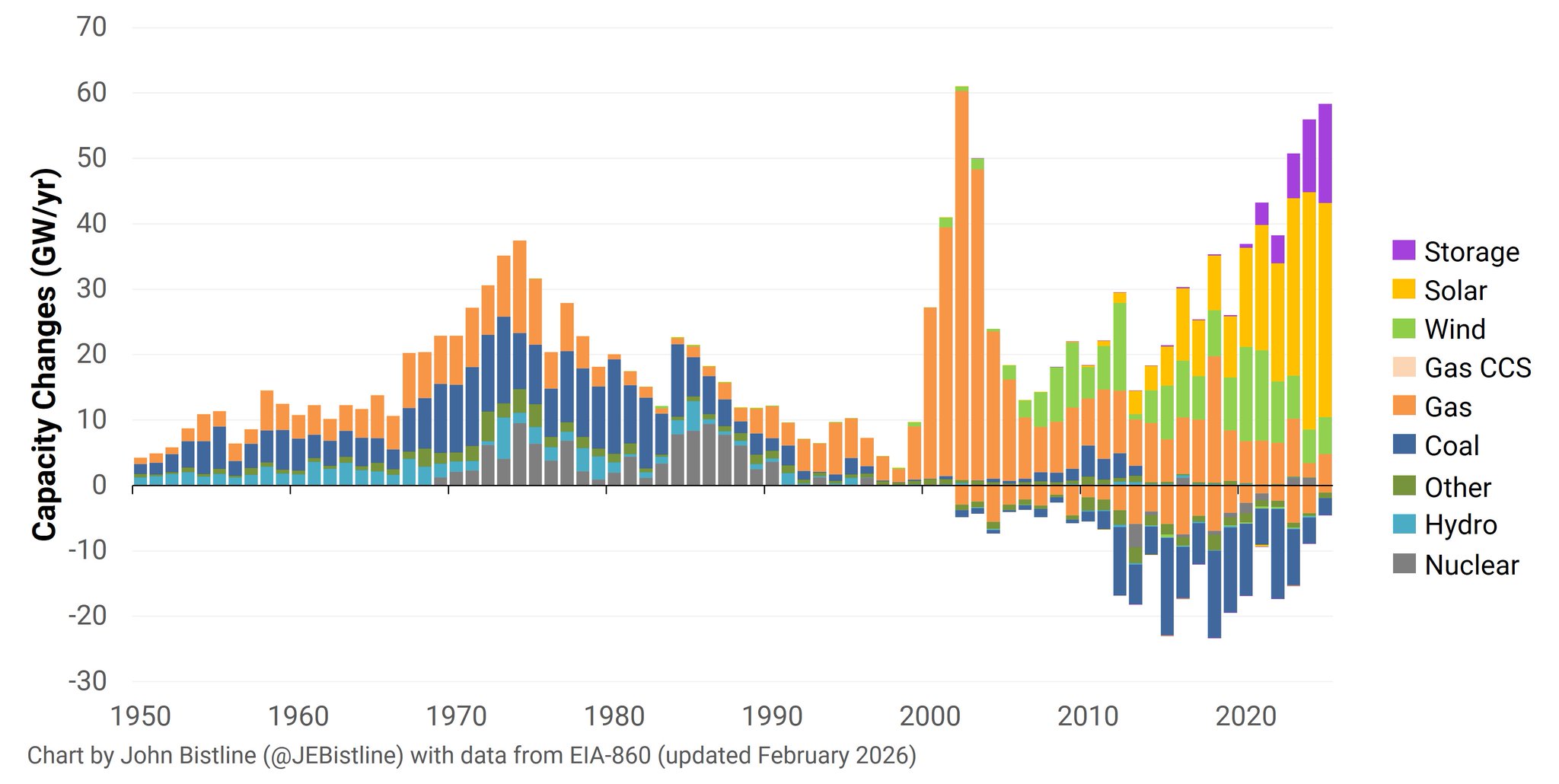

In 2024 and 2025, only about 50GW of capacity were added each year, not necessarily from sources that can effectively deliver their full capacity 24/7, which is what datacenters need. And you cannot rely on overcapacity in other states because:

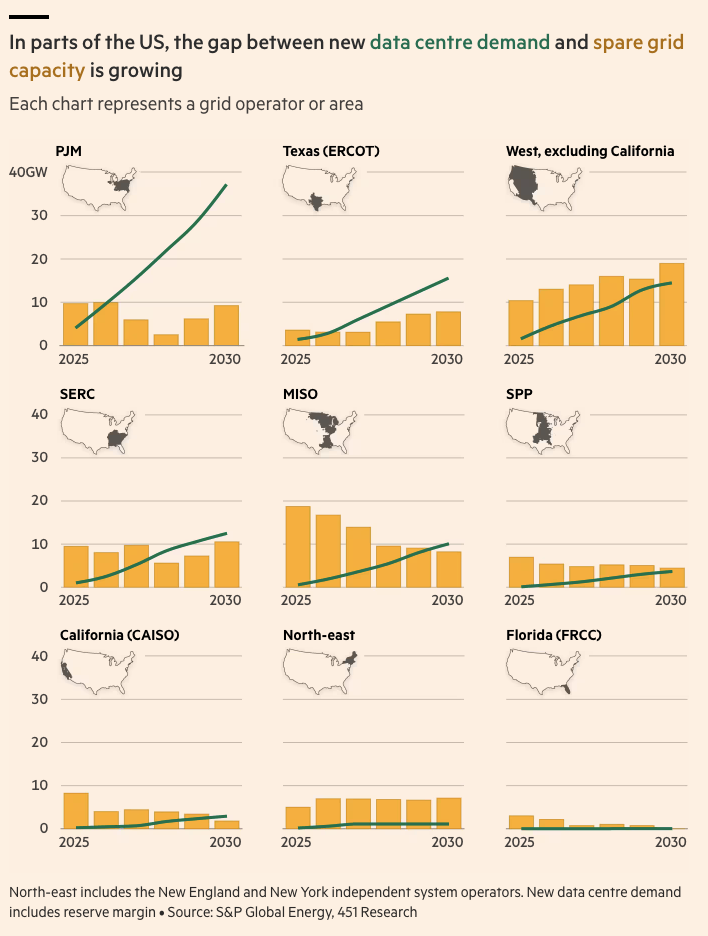

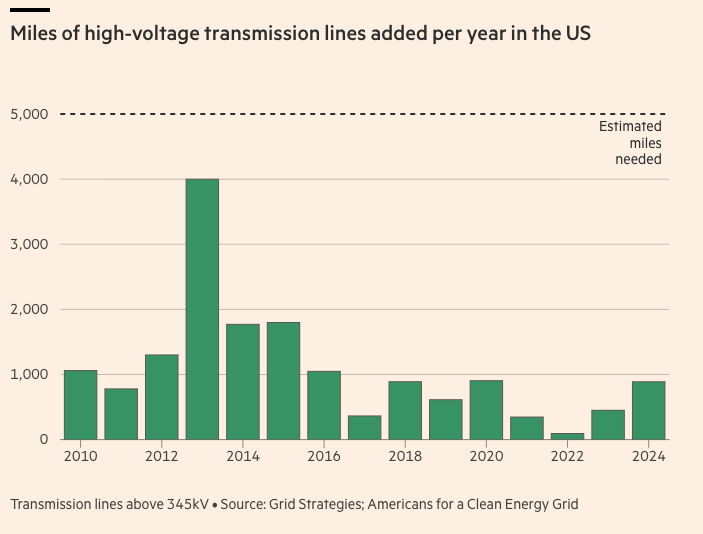

- The grid / interconnect infrastructure has been underinvested for decades and regularly breaks when the load is too high or too low. Transmission more than generation is often the bottleneck in the US.

- Even if it could sustain the load, 50GW of solar power a year is barely enough. This is the context of OpenAI’s letter to the US administration in October 2025, urging them to add 100GW of energy per year until 2030.

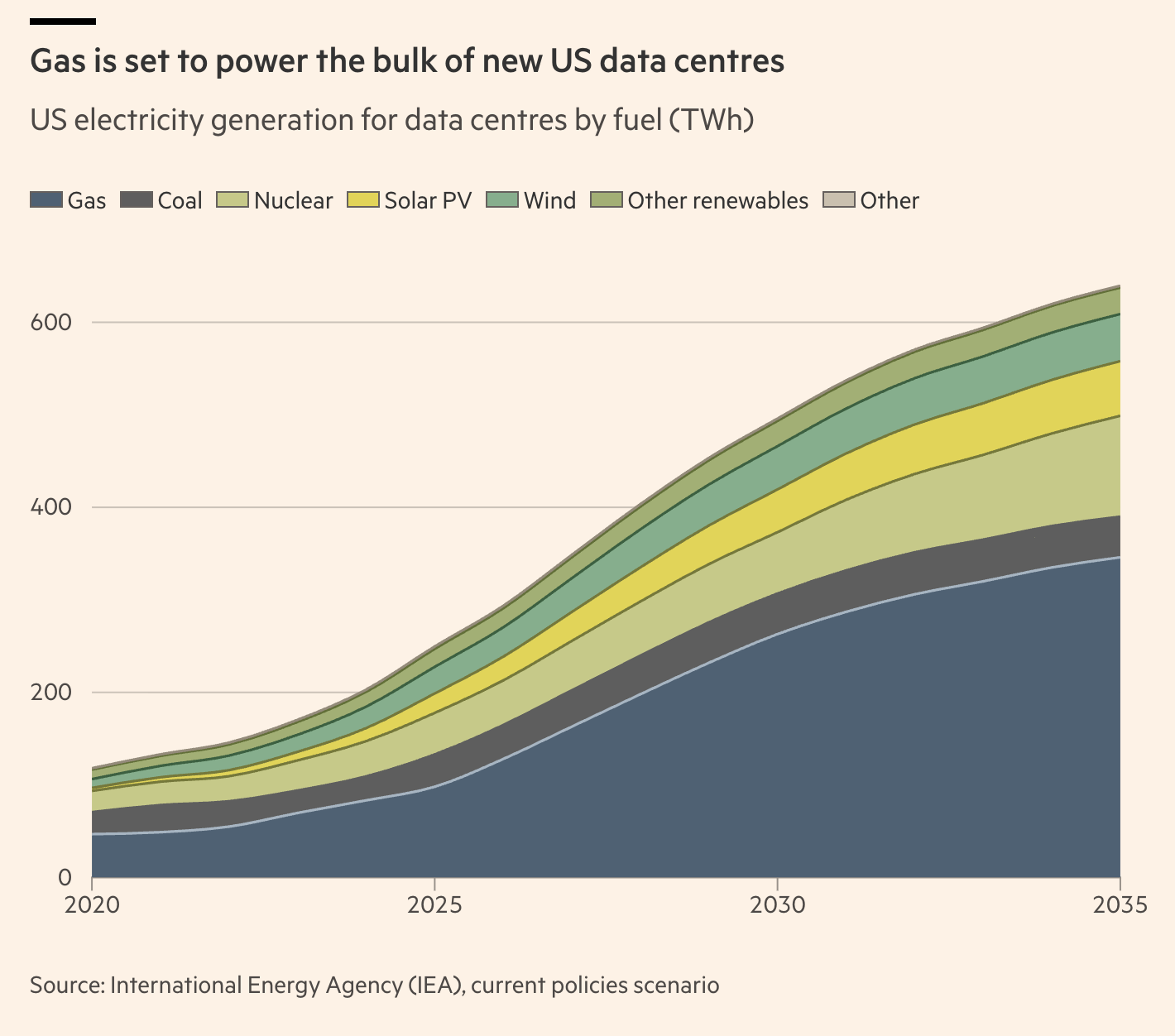

Let's pause to take a closer look at the chart on US electricity generation for datacenters by fuel. Part of the difficulty when working on energy consumption is that actual production is expressed in GWh or TWh, i.e watts produced during the 8,760 hours of a given year, so you need to compare 1GW of capacity used at 100% over a year to ~8.8TWh. When you consider that US datacenters used about 200TWh in 2024, this represents about 25GW of capacity if utilization is close to 100%.

Despite what I said about doubling or halving any figure to get to an acceptable range, this seems outside of what I’d consider acceptable if I compare this figure with the 51GW mentioned in the same FT article. The FT does not give much background to this 51GW figure. It may be for 2025, or more likely, it's still heavily skewed towards traditional datacenters (non-AI) which do not use their full capacity. In that case, it could make sense. Then, looking at the projections showing that US datacenter consumption will grow to 500TWh by 2030, this corresponds to about 35GW of additional capacity if we assume that new datacenters will largely be AI datacenters. Now 35GW seems low compared to what you see elsewhere. This may be because the OpenAI capacity is double counted everywhere else, or because the International Energy Agency (the FT’s source) is just more conservative in their assumptions. Overall, I believe that there are sensible explanations for potential inconsistencies in the FT article, and that’s why I highly recommend this interactive story(7) if you are interested in this part of the AI value chain.

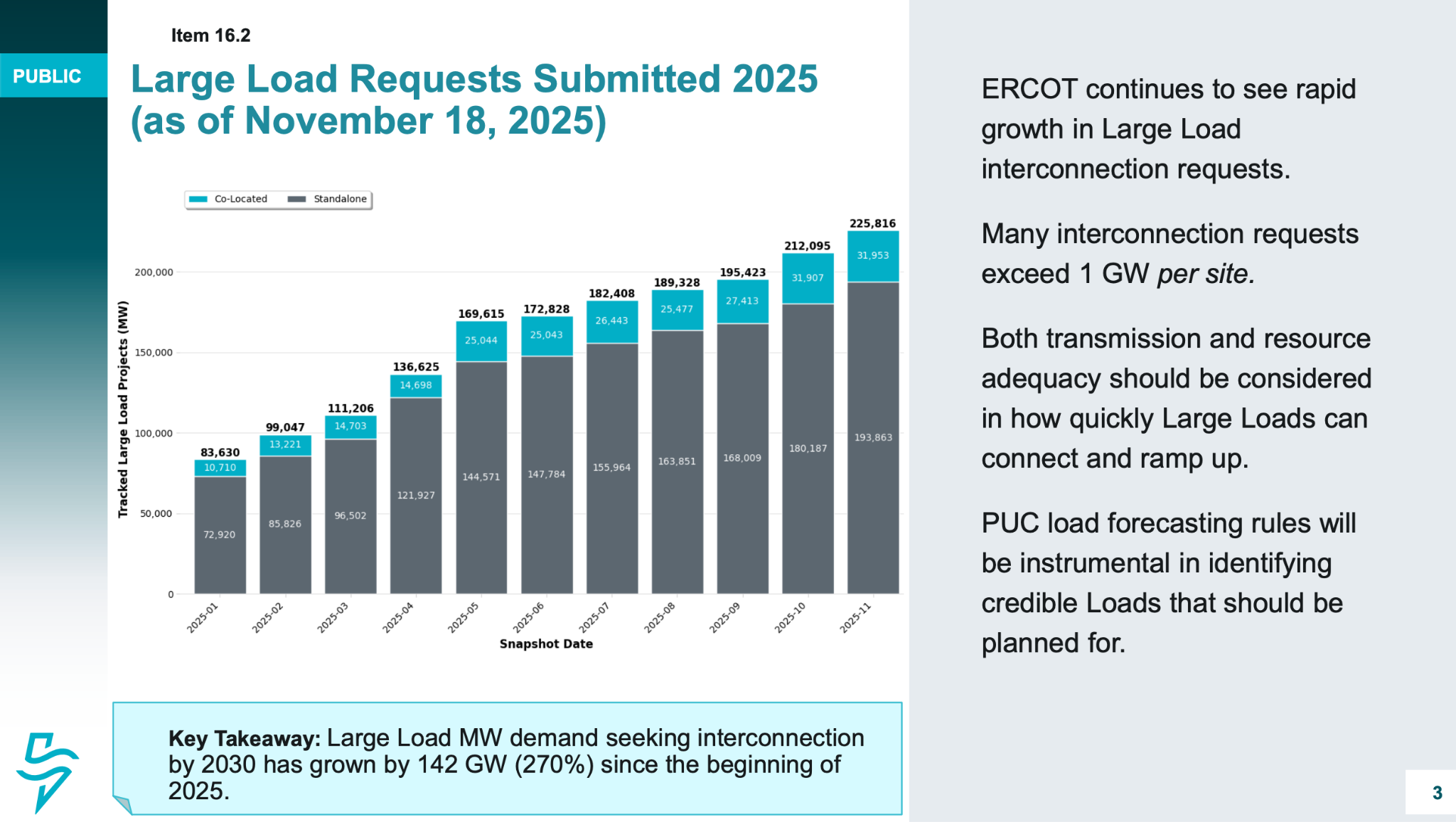

However, there are other cases where you see a chart on social media and feel like there cannot be a sensible explanation. For example, this chart on interconnection requests to ERCOT (Texas) shows that the queue is now over 225GW. Texas does have some spare capacity and electricity is cheap there but this number does not make any sense in the context of an overall US capacity of 1TW… let alone in the context of the peak load of 85GW in Texas! What happens is that companies file requests for several projects even though only one might eventually be built, or just file a request to hold a spot in the queue. The backlog for ERCOT is not actually 225GW. If I wanted to be facetious, I'd highlight that the current trends to offload assets in special purpose entities and to create an illusion of grid overloading remind me of the Enron days some 30 years ago. Look up Enron's Death Star or Fat Boy strategies, you'll understand what I mean, albeit it does not seem that one party profits from this trend in the same way today.

Industrial strategy

Even if you are on the conservative side like the International Energy Agency and expect only 30GW of additional compute capacity by 2030, it should be pretty obvious to you that it cannot just be “added”. Labs may get the hardware but they won’t get the power from the grid. What the capex reports show is the size of the pipes that may be built, not the actual flow through them. It is not even a case of outbidding all potential clients for energy: prices will surge everywhere for sure but at the end of the day, the production capacity is just not there. And without power, AI datacenters are merely warehouses for very expensive electronics. The traditional way of approaching such industrial strategic questions implies either of these two options:

- Only build datacenters in areas that have spare energy capacity and get in the queue to be connected.

- Build new power plants to increase the grid's capacity.

Option 1 is long and expensive but somewhat easier because you only have to deal with local bureaucracy (plus the usual logistics and supply chain issues). Option 2 is much more complicated as more administrations/agencies have to get involved, and if you envision more than just burning fossil fuels to produce electricity, you are looking at one of the most complex endeavors in terms of regulatory sign-offs.

Let’s put the sustainable options in perspective.

- The largest solar farm in the US has an installed capacity of less than 1GW. It’s really hard to exceed a capacity factor of 25% for solar power, which means that you’d need an installed capacity over 4GW plus energy storage solutions to power a 1GW AI datacenter reliably. We are talking about several millions of solar panels over a vast area... and a battery array many times larger than the current largest Battery Energy Storage Systems (BESS) in the world.

- Wind farms also take a lot of space, but this can potentially be located offshore. Offshore wind farms have their own regulatory hurdles, but they produce relatively more electricity than their land counterparts (capacity factor can exceed 40%, which is virtually impossible on land). The largest wind farm in the US has an installed capacity of about 1.5GW.

- The largest hydroelectric plant in the US represents almost 7GW of capacity. Hydroelectric power is highly dependent on water availability and rarely exceeds a capacity factor of 50%. The Hoover Dam (2GW) illustrates how various issues can compound and lead to a capacity factor below 20%.

- Finally, a typical nuclear plant generates 1GW and its capacity factor exceeds 90%.

The impossible build-out

Let’s go back to our bull-case where US players add 60GW of compute capacity by 2030. OpenAI’s recent deals alone represent north of 30GW(8). Part of this need should be powered by plants that are already being built, but the shortfall would still be over 40GW. It goes without saying that building 40 new Hoover dams in 5 years (assuming a 50% capacity factor) would be a silly idea(9) so most AI bulls envision going nuclear - literally - to power the AI industry sustainably.

You might ask: How much would the buildout cost? Does this come on top of reported AI capex or is it included? Well, it depends on what buildout and what capex you are considering. The devil is often in the details and the OpenAI deals are a perfect illustration.

Deals with chipmakers are typically in a range of $10bn-$15bn per GW. I personally don’t think that OpenAI's chip deals represent a fair market price because there are many other arrangements involved. There are a lot of moving parts given the different technologies and the current tension on supply chains, but I’d put the fair market price in the $15bn-$25bn range. Jensen Huang, Nvidia’s CEO, said in an investor call in August 2025 that deploying 1 GW of datacenter capacity costs between $50bn and $60bn, of which $35bn is for Nvidia chips and systems. If that’s the case, I’m probably undershooting in my mental model. The industry seems to converge on $50bn per GW. This includes the chips but also the infrastructure around it, including, among other things the cooling system and the temporary solutions to power the datacenter (see below), the backup generators, etc. The chips have a certain useful life which seems shorter than the rest of the infra, and the rest of the infra comes with operating costs. All this must be taken into account when considering the cloud deals around $50bn/GW per annum. If the chips’ useful life is greater than 3 years and provided that demand holds up, cloud deals can be very profitable for datacenter operators. But the phasing of the ramp-up of the various components can be critical given these companies often borrow to build the datacenters and there are billions at stake. Execution will be key, and not everything is in their control, so some project sometimes look like Hail Mary passes.

Oracle’s stock jumped by 25% after being promised $60 billion a year from OpenAI, an amount of money OpenAI doesn’t earn yet, to provide cloud computing facilities that Oracle hasn’t built yet, and which will require 4.5 GW of power

Micheal Cembalest (JP Morgan), Eye on the Market, September 24, 2025

The numbers given above do not include the cost of the actual long term energy infrastructure. To give a sense of the cost of a GW of nuclear power capacity in the US, the last two units of the Vogtle plant in Georgia (2024) cost over $35bn combined for a total capacity of 2.2GW. This can be amortized over a long time so cost may not be the main issue. Time is. Building a nuclear plant can easily take a decade from initial proposal to operations. Tens of them are required but there is only so much arm-twisting one can do to move faster. Overall, nuclear-powered AI feels a long way out.

Another consideration is that financing new power infrastructure is not at all equivalent to commitments for chips in terms of risk, even if the commitments are in the same ballpark in dollar terms.

As mentioned above, OpenAI deals are often mere MOUs for priority rights in a supplier order book. If it turns out that demand is softer than advertised in pitch decks, OpenAI and their peers will scale purchases down, irrespective of announcements made recently. Last year’s press releases and blog posts will disappear from websites, and new announcements will be made as if additional volumes were secured. This is how a good Press Release Economy works: the press release itself makes everyone proud, especially if it bumps the share price.

For power infrastructure, however, once the construction has started, one can’t just decide to build a third of a power plant and put out a carefully worded press release to boast about the achievement while hiding that a previous plan ever existed. Commitments are more tangible; they have a local impact. Risks are not only much higher, but the risk appetite of the parties involved - not quite VC bros out of San Francisco - is also much lower. In that context, capital coming from the infrastructure arms of Private Equity firms will certainly help. In any case, it will cost a lot and it will take time. AI Labs don’t have time. Remember: they must climb the hill fast to be as high as possible when the tsunami hits.

The fast and the furious

How to move fast? As far as infrastructure is concerned, moving fast implies not breaking things. And sometimes, restoring things. Microsoft and Google struck deals to fix and restart closed nuclear plants instead of building new ones. In each case, the capacity is below 1GW and the cost of restarting the plant is estimated to be in the range of $1bn-$2bn per GW. The hyperscalers have committed to 20-year purchase agreements. This is the cheapest and fastest path to nuclear power, but there are only a handful of closed plants that can be restarted.

Amazon takes a slightly different route by acquiring parts of existing plants and scaling them through Small Modular Reactors (SMRs). Their strategy is to build datacenters adjacent to these plants to source power directly (behind the meter) and thereby keeping much of the grid bureaucracy out of the loop.

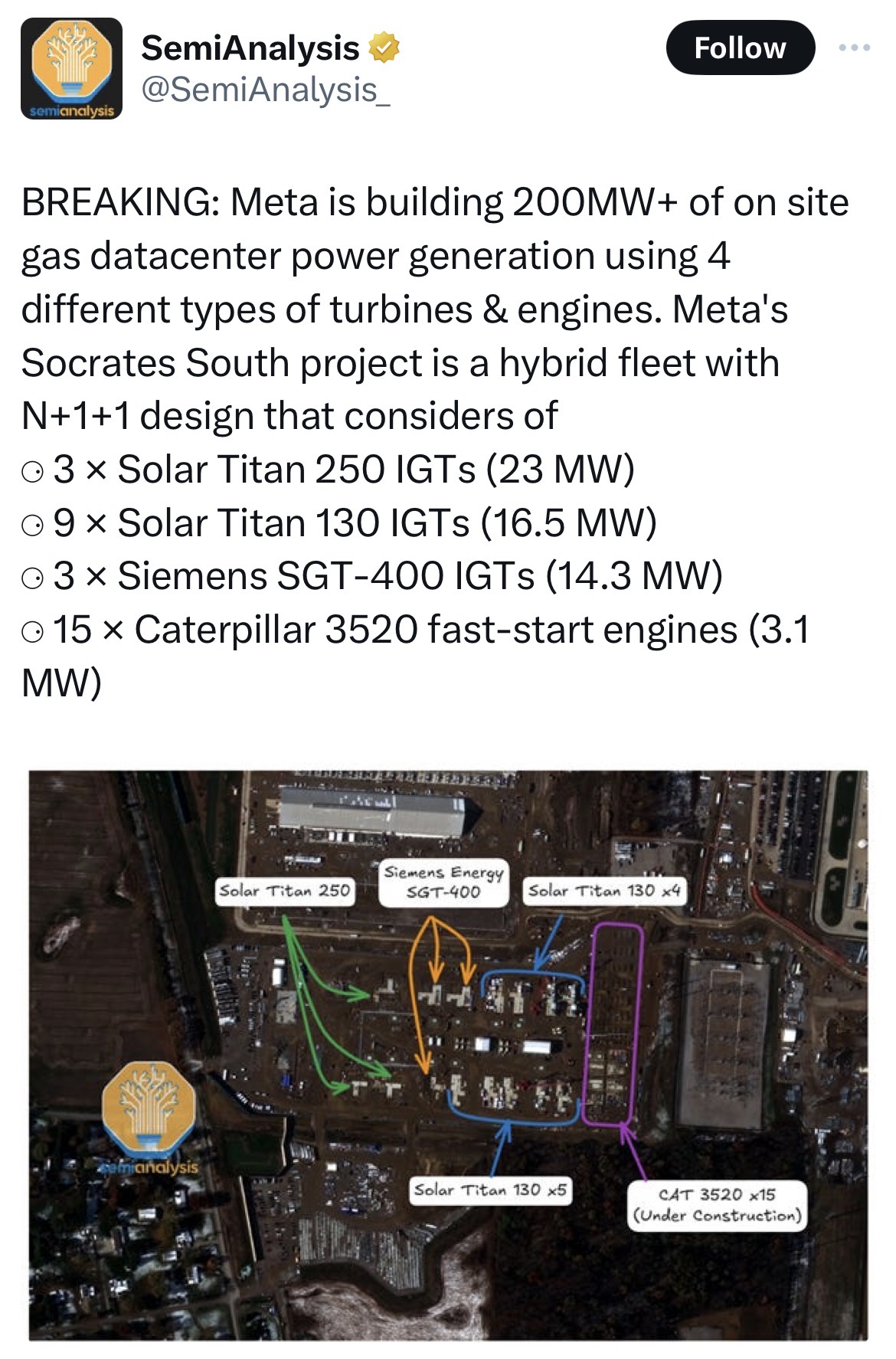

Elon Musk, who has a real talent for solving hard industrial problems (see Tesla and SpaceX), implemented a much faster strategy early on with xAI. Like Amazon, the idea was to cut out the middleman and to produce power on site, but xAI's approach relied on massive gas turbines. To bring their giant GPU cluster Colossus (100k H100 GPUs) online as soon as possible in 2024, xAI rented gas turbines, and it was presented as a temporary solution. But it does not look so temporary anymore, and given the convincing proof of concept, the strategy is being adopted by other players in the industry. Gas turbines are not really a sustainable solution - at least environmentally speaking - but they can be a viable solution in the long term financially, so gas turbines can be purchased instead of rented if the solution is deemed permanent.

Like for other components of the AI value chain, the global capacity of gas turbines (70-80GW?) seems fully booked out until 2028, pushing everyone to think outside the box. The FT reports that GE Vernova is supplying aeroderivative turbines that are expected to produce nearly 1 gigawatt of power for OpenAI, Oracle and SoftBank’s Stargate datacenter in Texas. It also reports that ProEnergy has sold more than 20 of its 50MW gas turbines directly adapted from jet engines. Sam Altman-backed aviation start-up Boom Supersonic also announced a deal to sell Crusoe turbines that are expected to provide 1.2GW of power.

Seeing jet engines being adapted and mobile gas turbines becoming critical components of the AI value chain takes me back to my previous life: I used to invest indirectly in infra funds owning power plants or components of the US grid but, before that, I focused on direct investment. And around 2017-2018 (probably), I received an inbound presenting me an investment opportunity as GE considered selling the [mobile] gas turbine business to PE. I didn’t really like it. I don’t think anyone did; I don’t think it was sold. If I have the timeline correct, this business unit was ultimately spun off as part of GE Vernova. I’m sure there have been ups and downs since then, but it must be so valuable today.

On-site generation does not fully alleviate the issue of getting approval from local authorities. For that too, Elon Musk’s xAI has demonstrated incredible pragmatism, by establishing a datacenter close to a State border so they could shop around and choose the most accommodating regulatory environment.

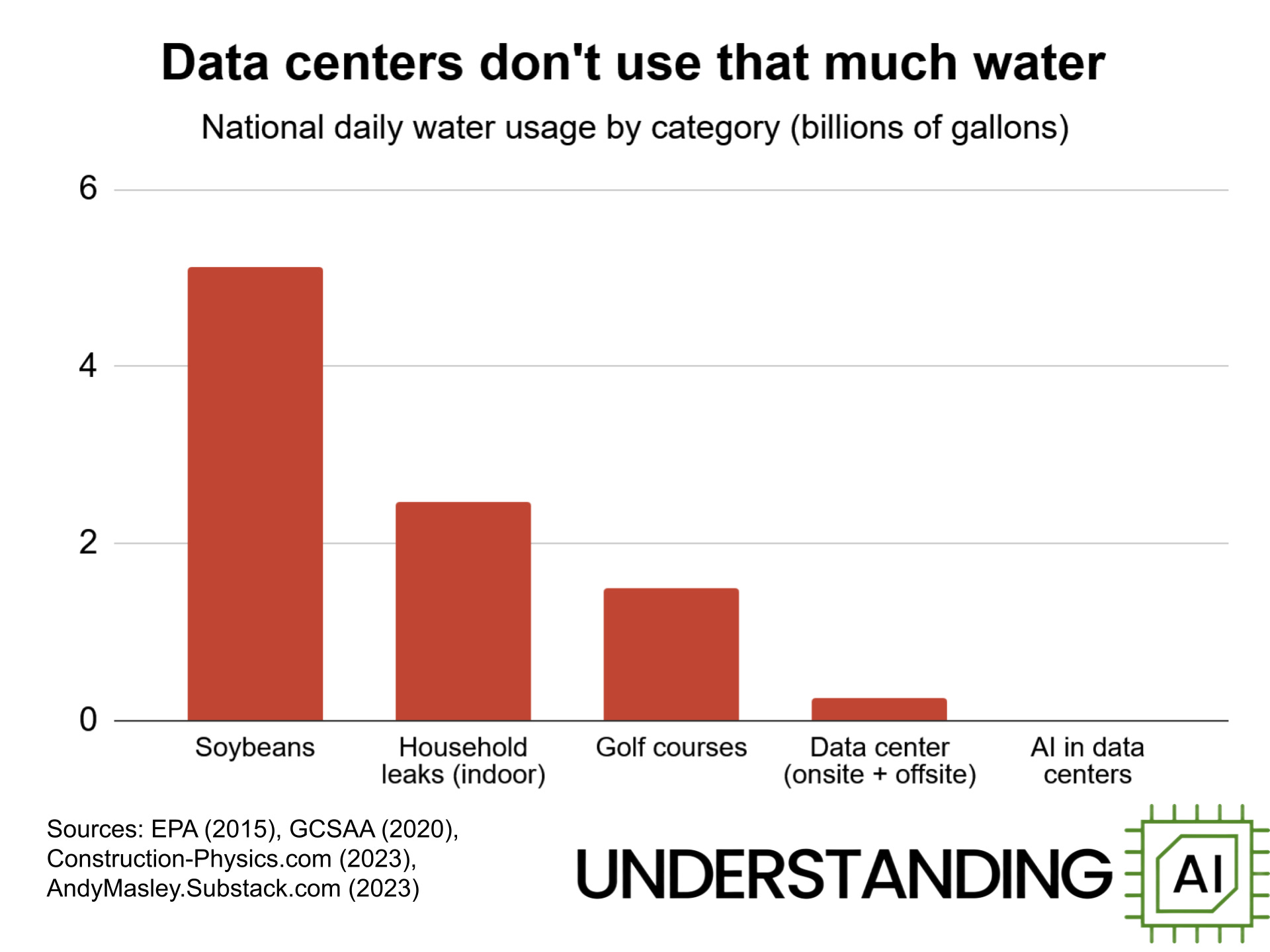

Water

I won’t make the same argument for water as for energy. Traditional datacenters heavily relied on evaporative cooling, which consumes vast amounts of water, but the AI industry had to turn to direct liquid cooling for higher efficiency (see below). This means that its water consumption is negligible compared to other industries… or even golf courses. Misinformation about AI’s gluttonous water usage was largely debunked in 2025, which was a positive development. This does not mean that AI has no impact in water resources: traditional datacenters still consume a lot of water, and even for liquid cooling using little water, the mere existence of a party who can outbid anyone to get water will cause friction.

The reason to bring up water now is that a parallel can be drawn with energy: where infrastructure is lacking, hyperscalers turn to on-site solutions for water treatment or contribute to the upgrade of public infrastructure by committing to multi-year purchase agreements that justify billions in investments by local authorities. For example, in Arizona, Microsoft agreed to invest in new local wastewater infrastructure and to build its own water treatment facilities to release clean, potable water instead of just using the sewer line’s entire capacity.

Datacenter cooling is also a good topic to close the loop with comments made about critical components that may not be strictly necessary in the future: to cool modern datacenters, the norm is now to use liquid cooling via direct-to-chip cooling or immersion techniques. These liquids, or gases resulting from a phase change, flow through a radiator (dry-cooler) to be cooled with air at ambient temperature, i.e. “air-cooled”. Evoporative water cooling is considered a legacy “technology”, only used when modern cooling solutions are not an option. Companies producing modern liquid cooling solutions obviously benefited massively from the current AI cycle. However, their stocks dropped in early January 2026 after Jensen Huang commented that their next generation chips could be cooled with water at 45 degrees Celsius. I’m not saying that the market reaction is adequate - it seems like dry cooler companies will be more relevant than ever even if the liquid itself changes or if the need for energy-hungry chillers (refrigeration) is removed - but it goes to show that we shouldn’t take for granted that all current components of the AI value chain will be as critical in the future.

Good bubbles, bad bubbles

My controversial opinion about bubbles is that there are “good” bubbles and “bad” bubbles. Good bubbles foster investments in assets that benefit the public in the long term, even after the bubble pops. Bad bubbles simply funnel pension funds' capital to a money-incinerator without any kind of positive by-product for society. AI justifies much-needed investments in infrastructure that would never have happened if it wasn’t for a few private companies spending at an unprecedented scale; AI is definitely on the right side of the line.

You may have jumped straight to this part of the post without reading the preceding sections. So let me reiterate what I mean by "bubble": I believe that the AI market is going to be MASSIVE, but I feel that it currently lacks important fundamentals, which I explained in detail in the second part of the post.

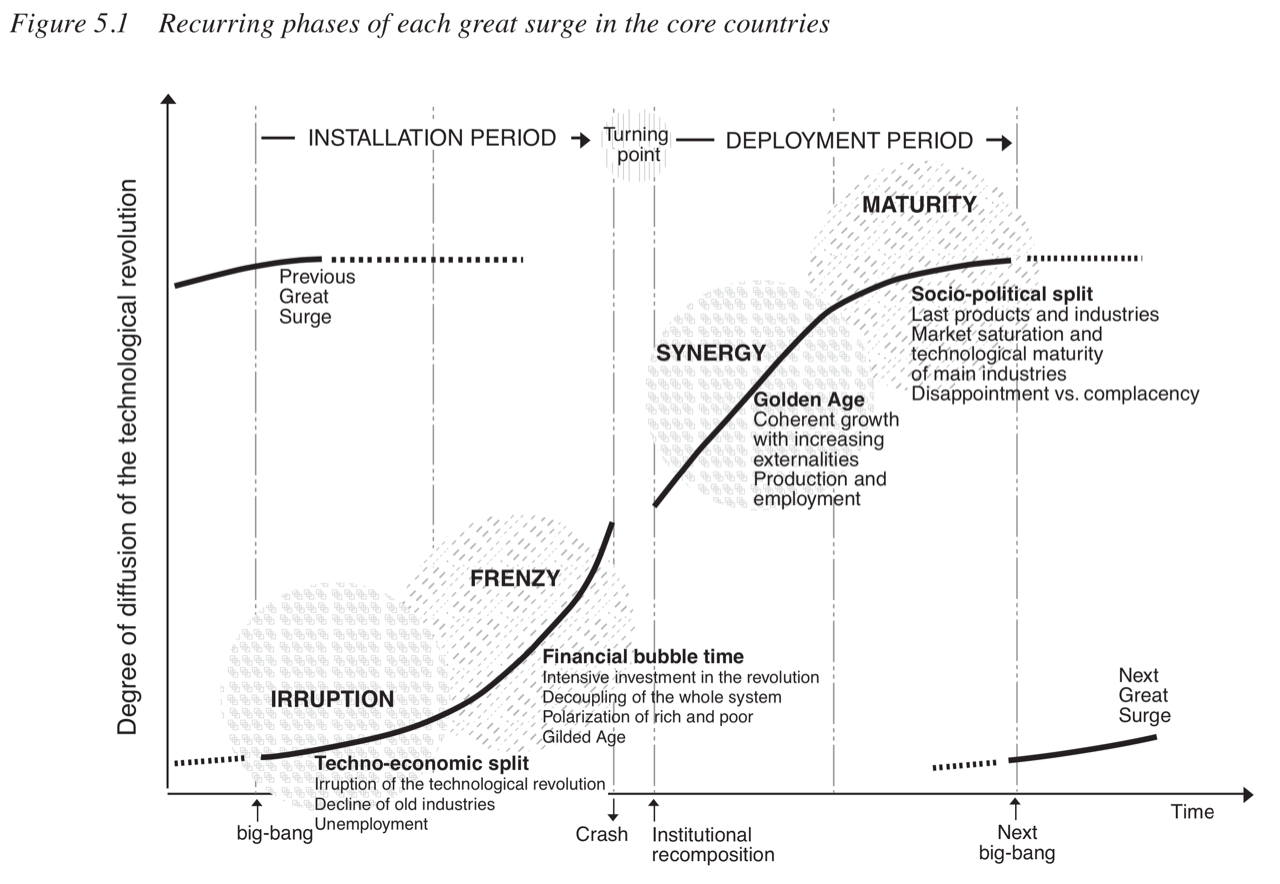

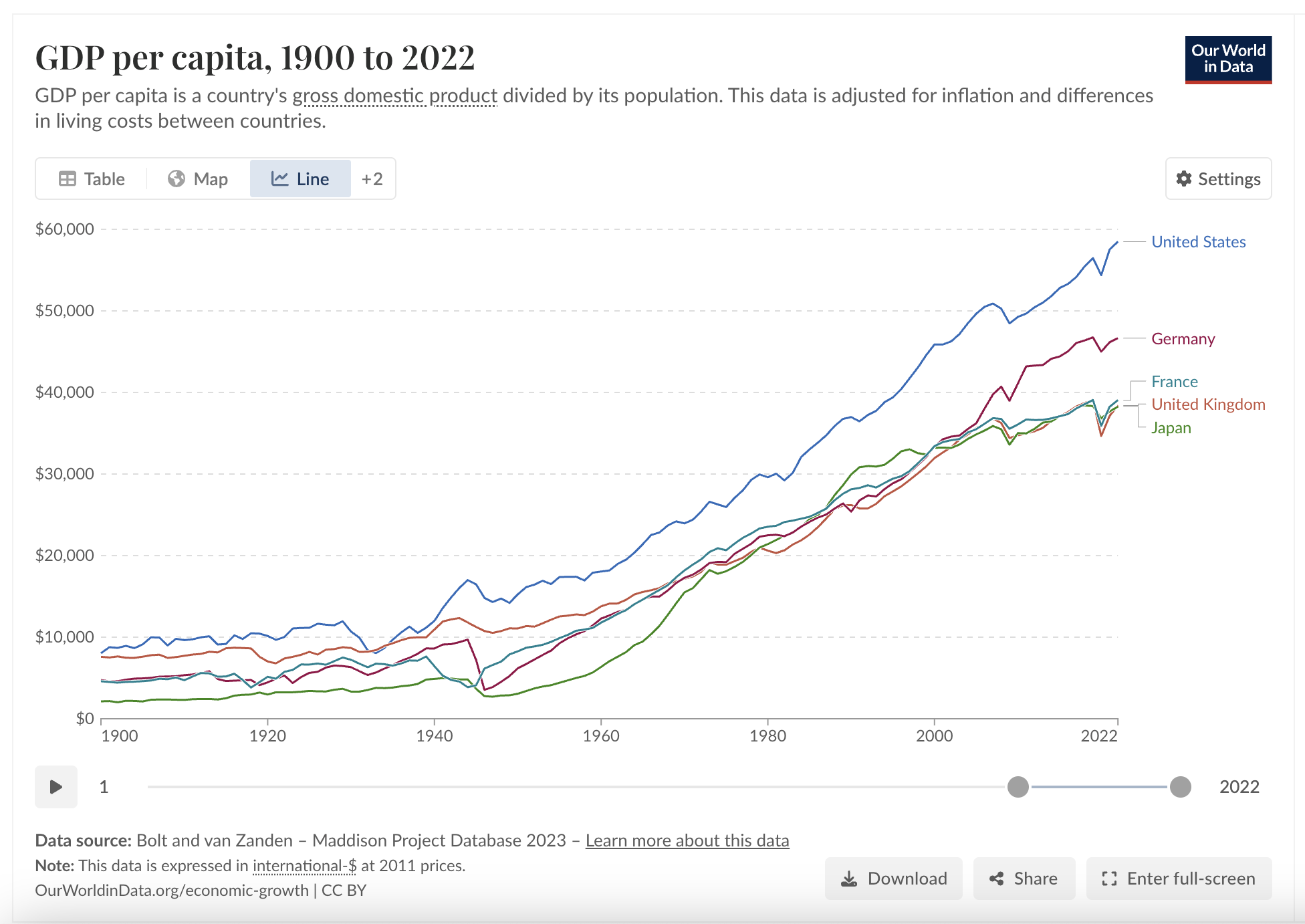

Carlota Perez’ framework on technological revolutions and financial capital(10) really resonates with how I conceptualize market dynamics in the early days of any technological revolution, not just AI. Perez’ framework includes a dichotomy between Financial Capital (Venture Capital, Stock Markets, Speculators - mobile and aggressive) and Production Capital (tied to legacy industries, inventory, and physical assets - conservative and slow to change). This echoes what I described in the previous sections regarding the tension between:

- Companies that raise billions to accumulate as much compute capacity as possible, effectively building very large but empty pipes

- Manufacturers of components that have to make trade-offs to fulfill orders, and energy companies that will fill the pipes

The technological revolution happens downstream of the pipes. Perez’ framework articulates a particular sequence of 4 phases leading up to the revolution, and this provides the perfect segue to the last part of this post. I started this blog series in March 2023, at the end of the Irruption phase, when the technology was demonstrated and Smart Money started moving. So far in this post, I’ve mainly covered the second phase of a “surge”, i.e. the Frenzy phase. Together, the Irruption phase and the Frenzy phase constitute the Installation period, which ends with a financial bubble.

My view is that there are financial or political incentives in the early days of any technological revolution that almost certainly lead to overcapacity. It happens all the time, everywhere. Market equilibrium is rarely reached through a gradual ramp-up. Participants don't stop investing simply because marginal returns are dropping across the market; they stop only when it becomes blindingly obvious that the market has crashed. Different financial structures across players and financial engineering prevent prudent, incremental progress at industry level because of information asymmetry. I also believe that it's increasingly difficult to urge caution because concepts like “winner-takes-all”, “network effect”, or “Moore’s Law” are so ingrained in the entrepreneurial culture that people refuse to accept that these concepts are not always relevant. Game theory convinced them that more capex will bring them closer to critical mass, at which point they will unlock unfathomable value because revenue will explode and costs will shrink. There is also an ego element to it as tech entrepreneurs are glorified these days. So they build because they can, right up until the system breaks. This part of the process corresponds to Perez’ turning point.

Trust the process

Interestingly, the financial bubble is not a bug but a feature according to Perez. She argues that mania is socially necessary. Without the irrational exuberance of the bubble, society would never raise enough capital to build the massive infrastructure required. For Perez, the bubble bursts not only because of overcapacity but also because Financial Capital just moves on. Financial Capital and Production Capital are always bound to decouple since they move at vastly different speeds. So Financial Capital goes to fuel the next surge and suddenly the entire ecosystem moves at the pace of Production Capital. To the outside observer, it often looks like progress has stalled, or even reversed, as Production Capital has to fight fires everywhere. This period allows institutions to catch up and establish the robust regulatory frameworks that are necessary for the Golden Age.

Perez’ theory is compelling, and it aligns with my own experience of these dynamics. I’d just clarify that this framework is only relevant for certain types of capitalist markets. The dichotomy between Financial Capital and Production Capital cannot exist in planned economies because Financial Capital does not exist in the same way: it is tied to the institutions; it cannot simply “move on”. Earlier in this post, I touched on the economic Darwinism of Chinese-style capitalism, commenting that the end state is similar to the Western approach: a bubble forms, then it bursts, and the few players that survive lead the actual revolution. The main difference is that the entire process is orchestrated by the central government in China:

- The technology to focus on is identified first;

- A clear regulatory framework is established (China has been a first-mover on that front);

- They borrow a lot of money at the central and regional level to fuel the surge and push private players to do the same;

- As seen most recently with solar panels and EVs, they build excess capacity so that prices fall below a sustainable level for all players but a few;

- The technology is commoditized, which means that it can be exported at scale but also - and that’s relatively new - that it's affordable for internal consumption;

- An important question now is whether Chinese developers will have sufficient freedom of application for the Deployment phase.

Both the Western approach and the Chinese approach obliterate billions of dollars by funding companies that will fail, but in both cases the process results in cheap technology that paves the way to a Golden Age and, often, new infrastructure that benefits the public. It is fair to say that I’ve been skeptical about the NFT bubble, but for AI I very much trust the process.

Is it going to be weird?

In Perez’ framework, the Golden Age corresponds to a Synergy phase where the new technology has become cheap and ubiquitous, and the infrastructure to use it is functional, so the real economy can build businesses on top of it. The Synergy phase is the first part of the Deployment period, which I think people should focus on instead of debating whether or not AI is a bubble. The bubble does not rule out a Golden Age.

“It’s going to be weird” is an internet meme used by early adopters when they realize that their daily lives will change materially once we really enter the Deployment period. I think it's misleading: hardly anyone will realize that the transition has happened. It’s only weird if you stay stuck in a past frame of reference. If you step back exactly six years: pre-pandemic life, working from home was marginal, video conferencing wasn’t the norm, you’d actually meet people in person all the time, and LLM assistants (even the OG ChatGPT) were inconceivable. By all standards of January 2020, today’s reality is weird, and I’m not even talking about the cultural shift around inclusivity, or today's geopolitical context. Step back 20 years: no smartphones, no social media; if you came straight from that era and sat on a bus today, you’d feel anxious seeing people around you staring blankly at electronic devices, ignoring everything around them. Step back 30 years: no Google, the Internet itself was in its irruption phase… and so on.

Would the 10-year-old me find today’s reality weird? Absolutely. Has the 40-year-old me ever felt weird about the reality I transitioned to ? No. And I am not special; humanity will adapt… because this is what this species does best. The permanent underclass is a myth but it does not mean that the transition will be smooth for everyone. However, it’s really hard to predict today who will be affected the most and how they will be affected because the technology is not mature - we are still in the Frenzy phase.

In that context, the best we can hope for is that institutions ask the right questions now so that, when Perez’ institutional recomposition happens, the new framework strikes the right balance between maximizing the positives for society and minimizing the negatives for affected individuals. You can’t neglect either of these objectives.

The current paradigm

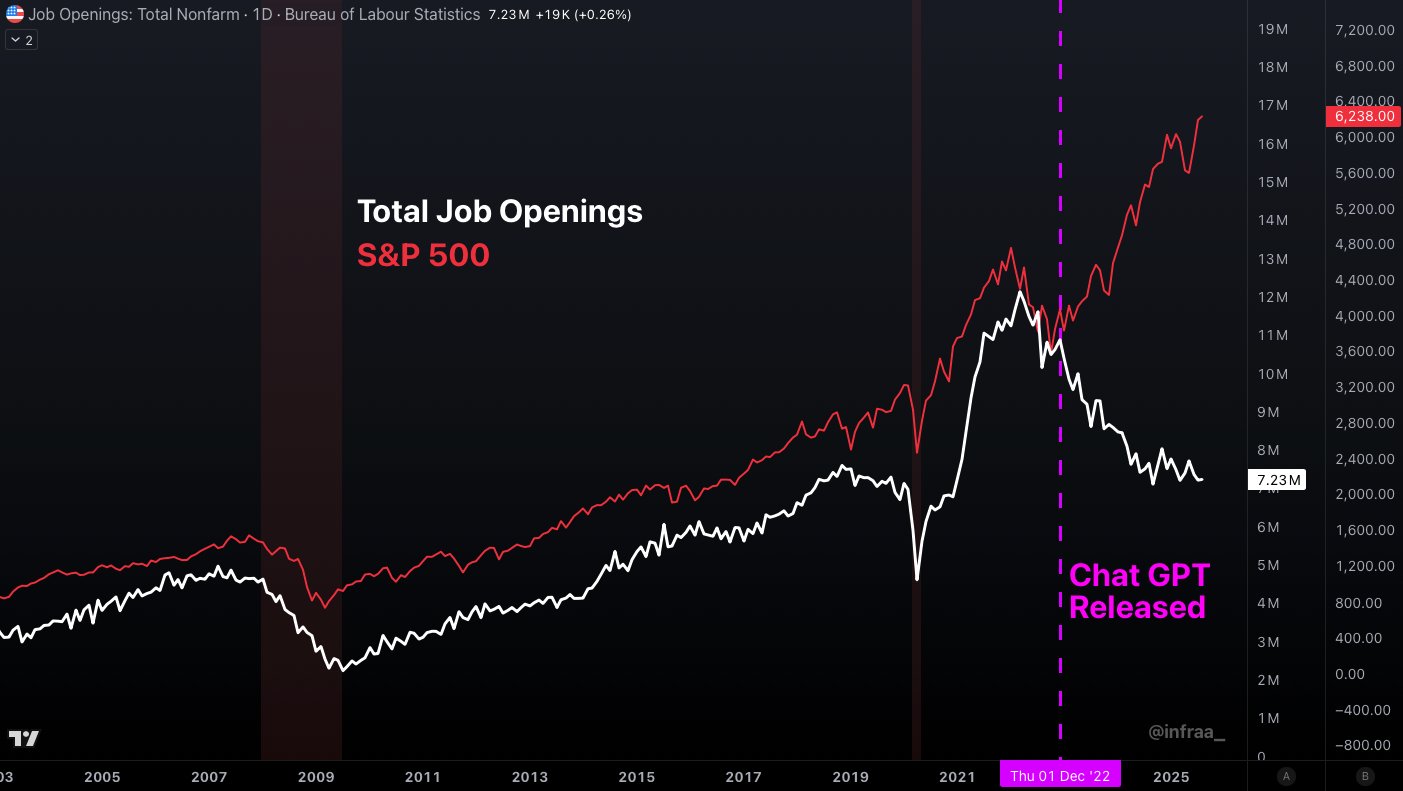

What’s on everyone’s mind today is the automation of white-collar jobs. The current state of the art in AI may not be the correct paradigm to analyze job displacement because:

- AI models/systems will continue to improve

- it’s hard to isolate AI’s impact on labor from other factors affecting the job market (e.g. high interest rates, macroeconomic headwinds, geopolitical uncertainty).

You may not get definitive answers in the current paradigm, but it constitutes a good enough case study to raise the right questions. And raising questions is precisely what you need to prepare for an institutional recomposition.

What if AI does not progress? How would this impact society?

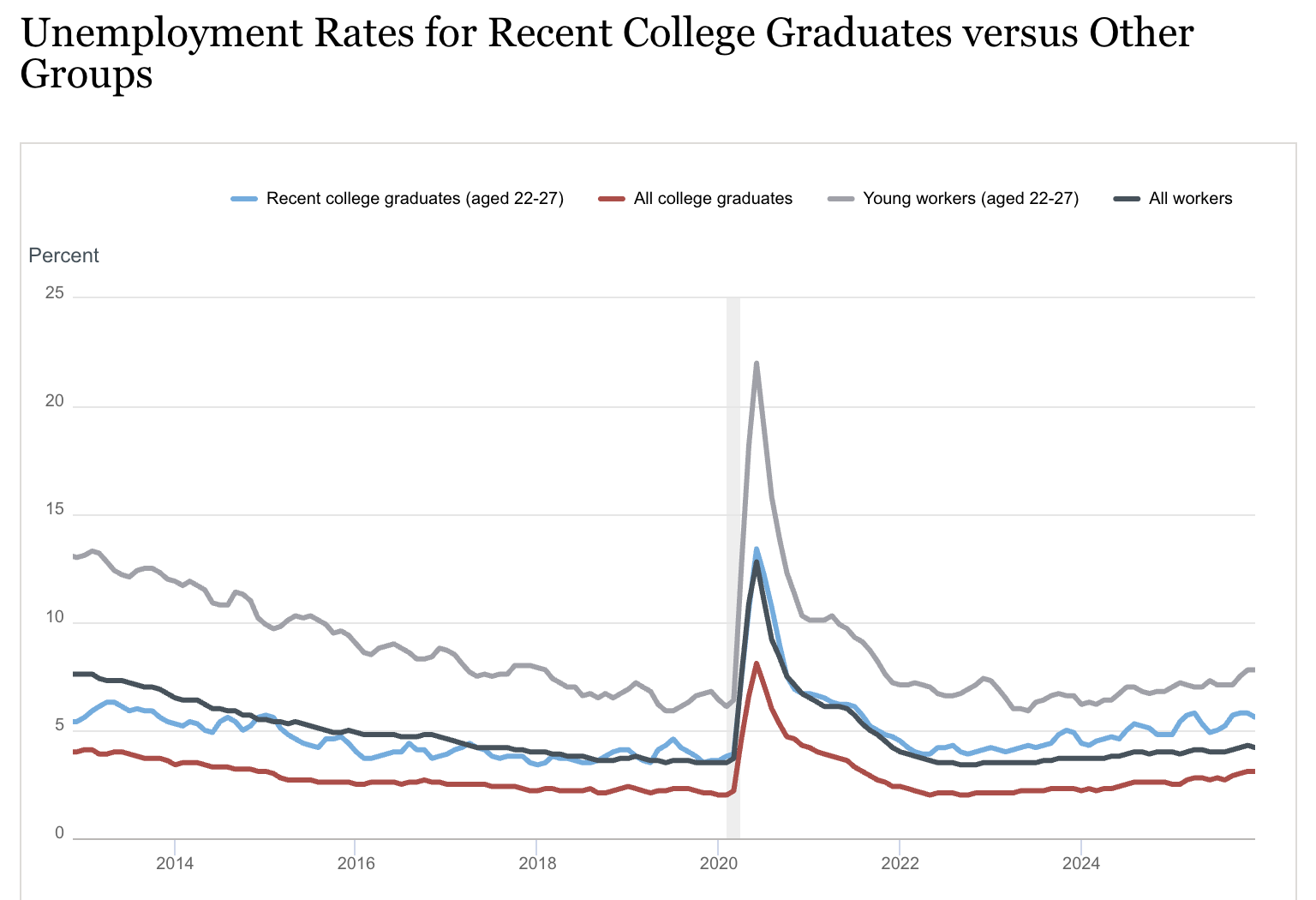

Some argue, based on the chart below, that AI is already wreaking havoc in the labor market. This claim seems largely exaggerated(11) because it ignores the terrible state of the real economy since the end of the zero-interest-rate period in the second half of 2022. The macro economic context means that companies are reluctant to hire and will leverage any tool available to avoid adding headcount, including AI. Current frontier models can largely automate away many tasks typically assigned to juniors in white collar jobs, which could explain why this demographic is hit the hardest. In 2025, multiple datapoints from recruitment platforms seemed to converge on a 40% reduction in job openings volume for this demographic. At the time, these statistics could be dismissed as mere anecdotal evidence, but official statistics recently came out, showing that unemployment for university graduates has reached multi-year highs in the US (excluding COVID).

The bell curve paradox

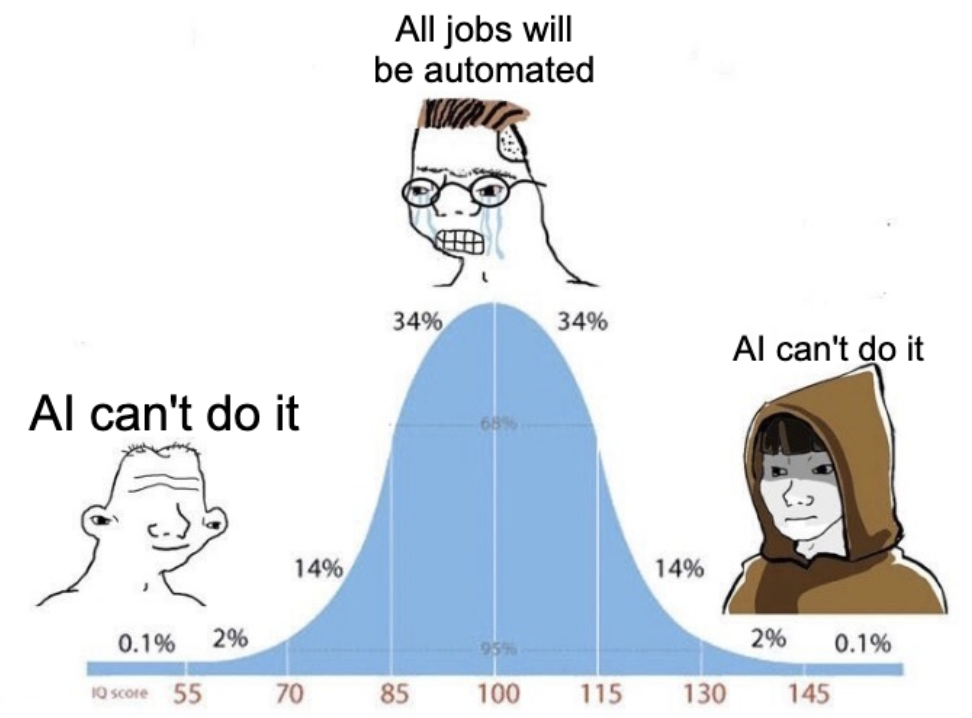

Given my background, I’ve always been inclined to measure models' capabilities in terms of how the output compares to what my analysts or interns used to provide. My experience is that, while capabilities have steadily improved across the board, a major contradiction persists: AI systems perform on par with or better than a junior in most tasks (and do it in minutes instead of days) but they fail at very simple tasks that humans nail 99% of the time. I am not talking about hardcore financial modeling, just basic chart reading or random hallucinations that poison the final report. I called this contradiction the bell curve meme paradox because models hit a wall at both ends of the IQ curve.

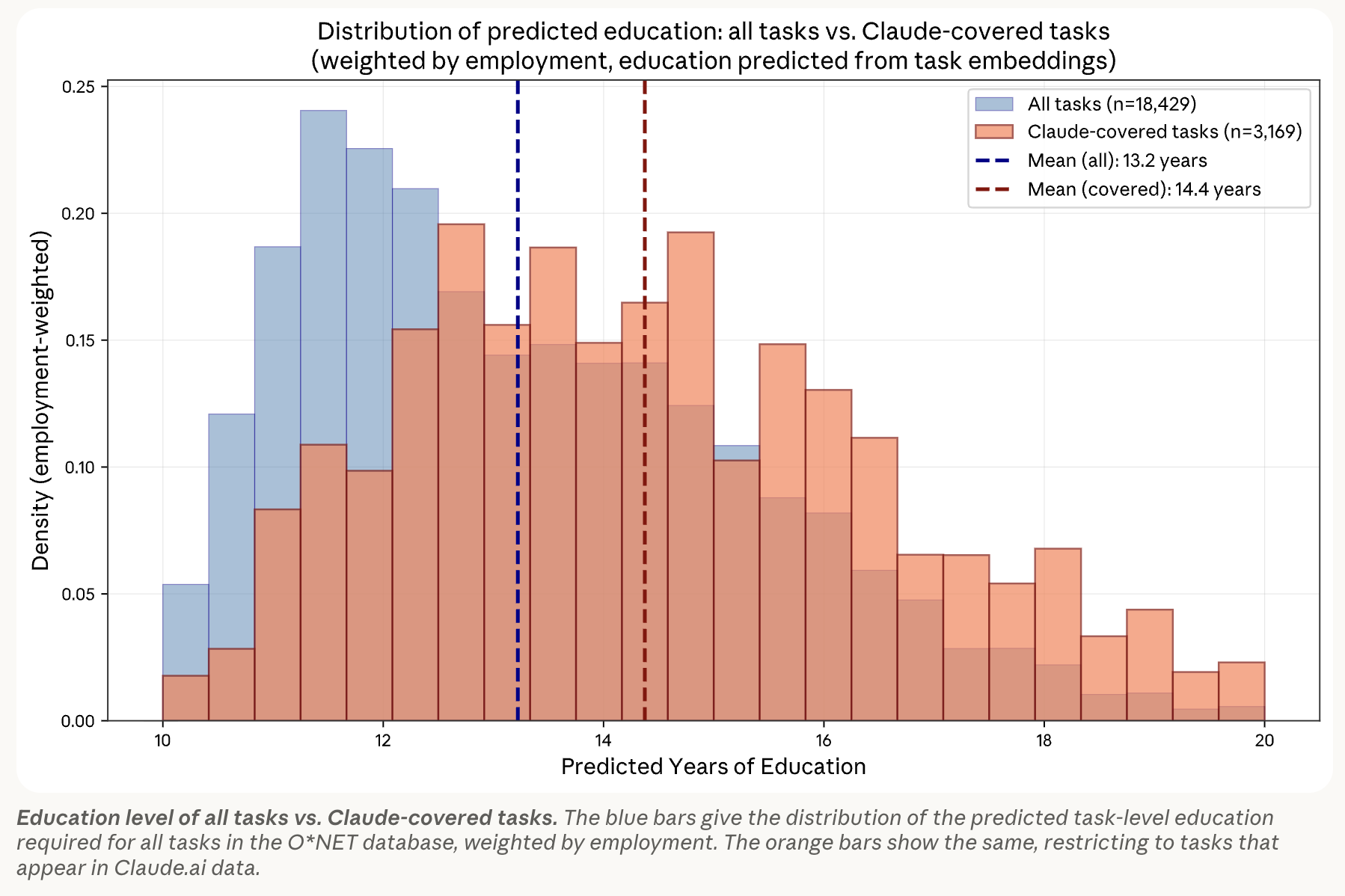

I’m surprised that the problem persists. I can’t tell if it’s just because these tasks are so basic that no one ever bothered writing a how to on the internet, so the model has no knowledge of them from pretraining, and labs do not deem these tasks sufficiently high-value to fix the shortcomings at mid/post training stage. In a recent paper, Anthropic mapped Claude’s usage by years of education required to complete the task. I felt vindicated when I saw a bell shape: users simply do not use Claude for the most basic tasks. It could be interpreted as “they use another AI system” but I think this chart shows that humans have quickly learnt that using AI is counterproductive for the simplest tasks.

Human in the loop

In the current paradigm, you cannot remove the human from the loop unless the job is merely a collection of tasks that are cheap to verify. For the avoidance of doubt, if you need a human trained for years to verify the output, it’s not cheaply verifiable.

I don’t hold this against AI: I used to review all my juniors’ work, and there were always comments. There are other surprising similarities, in particular regarding interns, as the lifecycle of AI models is relatively short so there is a frequent turnover like for interns. You may not face the headache of hiring a new intern (who might not be as good as the last) but you may have to go through your internal procurement process. In some cases, you may be worse off with an AI model, in particular if it’s not run locally and there is a risk that the provider discontinues it. On the plus side, AI systems work much faster and would do most of the work better than any junior (except very basic stuff and financial modeling in my case). If you can augment your juniors with the best AI systems, the ideal setup seems to only require 1/3 or 1/4 of the headcount. Financially speaking, it’s a no-brainer. And this alone could put immense pressure on the labor market.

In this setup, the value of the remaining humans no longer lies in their ability to complete tasks, but in their ability to extract value from the system. This is basically what managers do, except that in Human-AI tandems, the human sometimes needs to be the assistant of the AI system (simple tasks(12), taking shortcuts in internal procedures, etc), not only its supervisor. More experienced people may be better suited for this new setup than fresh-out-of-university profiles… or they may never adapt because they’ve forgotten how to do things and how to learn new skills. I don’t pretend to know how different demographics will be impacted; it feels difficult to predict. In any case, this new way of working would force us to rethink traditional hierarchical pyramids. The Human-AI tandem does not necessarily imply only one human and only one AI agent; some humans may be able to manage several AI agents, which would likely require a pretty large breadth of skills in the first place. Even in the current paradigm, because Human-AI tandems can be more or less scalable depending on the job, it is clear that not all industries will be affected the same way.

Critically, in Human-AI tandems, humans remain essential. And each human is individually many times more productive than before. It doesn’t matter if they only do 1% of the work: if this 1% is critical to the outcome, then the value of the human increases massively. Salaries will rise for the few who remain, and if demand is elastic, then many will remain. We have seen it in the past with lawyers: as computers enabled longer, more complex contracts (perfectly illustrating the Jevons paradox), humans who could handle the new level of complexity became more valuable. With AI, it may not even be about humans capabilities but about being held accountable if anything goes wrong. The responsibility of AI agents will be one of the most important topics to tackle as the technology matures.

AI responsibility

Let’s envision the next paradigm, when AI agents are robust enough to handle 99% of the tasks in a way that makes economic sense. Making economic sense doesn’t only mean not burning trillions of tokens every day, but also avoiding hacks that could potentially negate all the value-add. These hacks can take many forms; prompt injection is an obvious one today, but many more of these flaws will likely emerge. A key question will be whether this risk can be priced at all, or if the frequency and magnitude are too unpredictable. In any case, it does not feel impossible that, at some point in the future, the economic viability threshold is met and swarms of agents could run, autonomously, organizations operating in the tertiary sector. Then many AI-run organizations could interact to generate economic output without any human intervention.

You might ask: why would there be several such organizations if swarms of agents can do anything? In the tertiary sector, specialization was largely motivated by an optimization of labor (see Triplett & Bosworth on fighting the Baumol’s cost disease). But if you remove the labor, capital is the only limiting factor. I don’t buy into the argument that money and capital will be rendered useless in the future. The price of intelligence might drop to zero for most people (if they can’t take more), but for industrious people with capital and energy, it always has value.

The scenario where swarms of agents run the entire tertiary sector on behalf of individuals or organizations, while technologically plausible, would be at odds with existing legal frameworks for any economic activity. There are in fact several issues that would need to be addressed as part of an institutional recomposition, all of which relate to the concept of responsibility. Before diving into that, let me clarify that legal systems vary greatly across the world and analyzing how AI affects the concept of responsibility in the different systems would deserve a 50-page paper, so I’m just going to focus on what the main Western systems have in common.

- let’s take the simple example where an individual delegates all their admin work to a swarm of agents. Irrespective of the legal framework, that individual will be held liable if anything goes wrong and the agents cause damage. The potential liabilities are uncapped. Historically, this type of problem has been addressed by giving legal personality to companies or entities which would conduct the operations in their own name, and this created a legal shield for the individuals running or financing the entity. No such thing exists for AI assistants.

- You might think that the scenario described above is less of an issue for swarms of agents running organizations because a failure of the agents would be no different from a failure of the organization itself (the agents would be behind the corporate veil). An interesting question, as you go down that rabbit hole, is what happens to the reasonable care of organizations’ executives? Organizations must have executives; that’s why there will always be humans at the top of the pyramid unless legal frameworks change. So what happens when the executives are sued by shareholders and admit that they have no idea about what’s going on in the organization, because no one can track, let alone understand, it ?

- Another issue is that it's virtually impossible to prove why an agent process failed. These are not deterministic systems, and so long as these systems rely on token probability distribution and sampling, model providers will always have an out if you try to pin a fault on them. For now, they settle lawsuits to avoid bad publicity, but they fundamentally don’t have to. Organizations using bespoke solutions leveraging open-source models will literally have no one to turn to. In a multi-agent setup, another obstacle to tracing back an agent’s error is that the context processed just before making the error can come from many different sources, including other agents, and it seems very hard to isolate the impact of each of these sources.

I am certain that none of this will deter hardcore AI optimists from fulfilling their techno-utopian fantasies, but the legal uncertainty seems too high (for now) to build a compelling case for the next paradigm - even if technically possible - scaled at the level of society. The US legal system, ironically, seems particularly inadequate. To me, this system creates a selection bias by deterring the most sensible people from committing to anything meaningful (well executed and at scale), so it leaves only the “move fast, break things” type. This puts the entire field at risk: given Humanity’s exceptional track record at eliminating any form of threat (predators, diseases…), making sure that AI isn’t perceived negatively seems critical, otherwise the AI opportunities will be nipped in the bud one way or another.

Economic analysis