Ken Rogoff, former chief economist of the IMF and professor of Economics at Harvard, went on the Dwarkesh Podcast to discuss upcoming economic challenges for the two super powers of the 21st century: China and the US. The video and the transcript are available here.

This is the type of discussion that fascinates me because it highlights the deep rift in how people talk about China.

On the one hand, China's technology in key sectors now rivals or even surpasses its US counterparts, and its top-tier talent pool is unparalleled in both absolute numbers and skill level, so China seems to be on an unstoppable trajectory. That's what Tech Twitter is excited about(1) and what Finance Twitter refuses to recognize. I am not sure Rogoff himself recognizes this; his on-the-fly underestimation of China's nominal GDP as a proportion of the US's seemed telling.

On the other hand, China has a major debt problem that seems very challenging to solve, even with fiscal policy. Both arguments can be true: China appears doomed for the reasons Ken Rogoff mentions, but not only for those reasons, and it also appears to have built up sufficient momentum to challenge US global hegemony in all sectors.

The Looming Debt Crisis

Ken Rogoff opens with China, but the discussion on how to solve the public debt issue is ultimately relevant for all countries. In fact, most of the podcast focused on the US economy.

One very important point Ken Rogoff makes is the distinction between a financial crisis and a [sovereign] debt crisis. A financial crisis is a private-sector meltdown, where the appetite for risk drops sharply and no one is willing to extend financing (in any shape or form) to businesses. Ultimately, the lack of liquidity causes the system to stall.

Since the Great Depression, governments have developed a standard way to address this: bailouts. Monetary policy has been used extensively and will continue to be used until the system breaks. Rogoff quotes Milton Friedman on the Great Depression: “You didn't print enough money. You tightened the money supply too much.” This idea is the cornerstone of the dogma surrounding monetary policy: the money printer is a magic wand, and you will regret not using it. By doing so, governments inject liquidity into the system and, to some extent, keep the economy on track. Ken Rogoff points out that even though disasters are avoided, there always are long-lasting effects, and economies never fully return to their pre-crisis growth trajectory, unlike what happens after demand-induced shocks. There is a permanent drag. This process also transfers liabilities from the private sector to the public balance sheet.

I completely share Rogoff's analysis that we are not yet at the stage where governments will try anything other than throwing more money at problems. This is especially true for countries whose currency is in high demand, like the US. Appetite for their debt keeps rates low even as leverage increases. As a policymaker, if you manage to strike the right balance, the solution looks extremely palatable. Pouring liquidity into the system can drive inflation, which in turn mitigates the debt problem in real terms.

In 2022, the spike in inflation across the world was attributed to the war in Ukraine affecting energy and commodity prices, but I am not entirely convinced. With all the liquidity poured into the system to support the economy during the pandemic in 2020, I fully expected a massive spike in inflation within 18 months. While the war in Ukraine was a contributing factor, it conveniently allowed policymakers to divert attention from the more direct role that unprecedented monetary expansion played in fueling inflation.

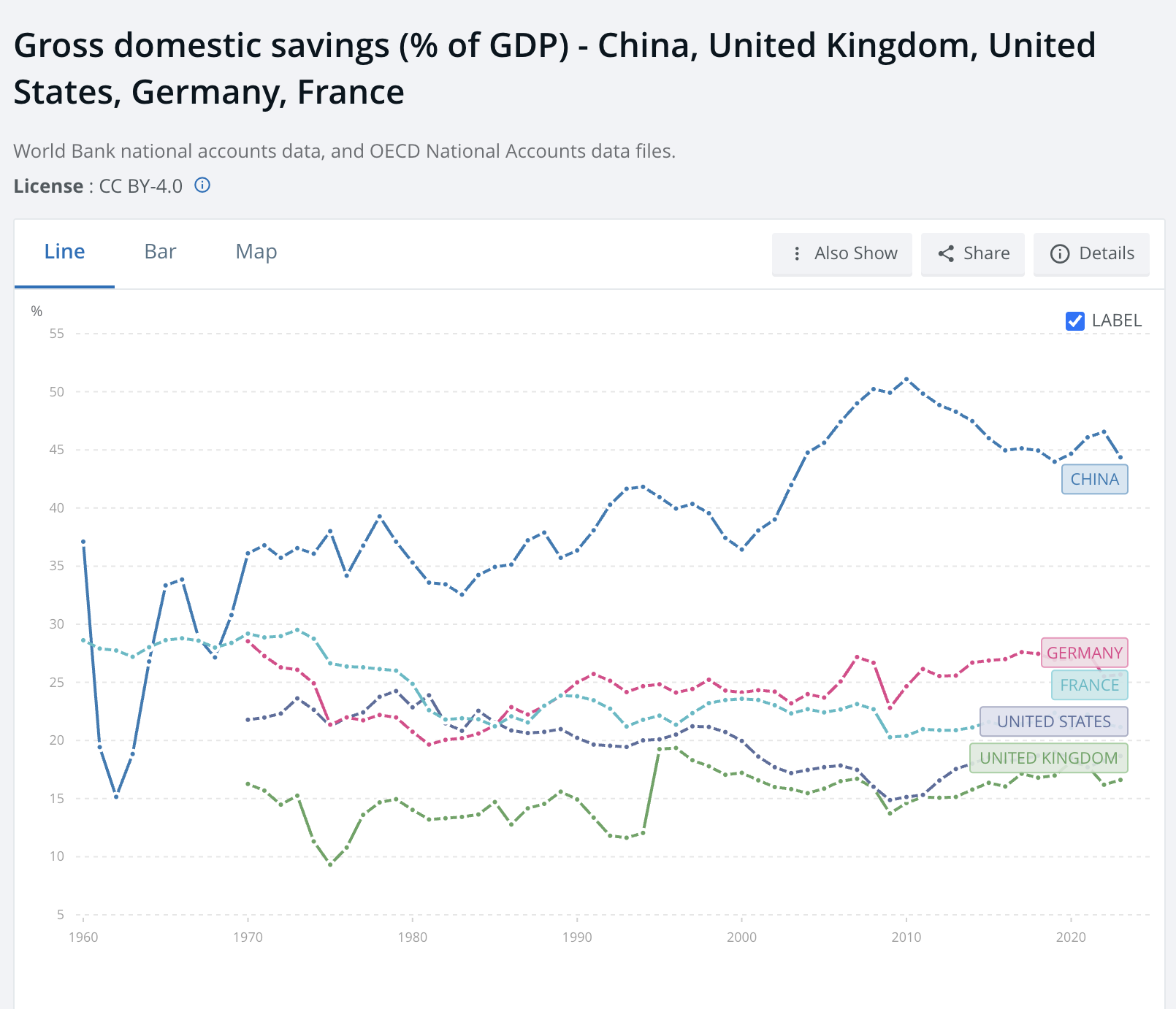

Banking on future inflation to solve current indebtedness is also very palatable for politicians because it pushes the consequences decades down the road, long after they have left office. Rogoff hinted at this when he mentioned that Xi Jinping inherited the situation from Hu Jintao. But Xi didn't really try to solve it, except by trying to outgrow the problem - capturing more value from supply chains (moving up the value chain, deeper tech, energy, etc.) - and ringfencing the economy to avoid becoming collateral damage from other countries' financial issues. China seems deep into the financial repression stage, as Rogoff points out, and this is in my opinion partly attributable to their culture, and partly due to the fact that they can't pull the inflation lever. Their problem is that the usual inflationary escape valve doesn't seem to work, as the country's uniquely high savings rate stifles consumption.

Looming over all of this is the demographic time bomb, and that is not unique to China. Many highly indebted countries that issue debt in their own currencies will be exposed to the deflationary pressure of aging -and ultimately contracting -populations(2).

I am not sure why so many economists seem completely blind to this fact. Dwarkesh's questions brought up the topic of deflation in the context of AGI potentially driving prices down, but Ken Rogoff's response, like that of most economists, focused on the typical effects of technological revolutions. He didn't seem to envisage that this time could be different because of: 1) the nature of the revolution itself (even though I am not completely sold on the "foom" scenario) and 2) other deflationary forces at play that seem extremely difficult to counter. My concern is that you could end up in a situation where countries continue to print more money and interest rates rise as a result… but inflation does not follow.

The US is probably the most protected from that scenario for many reasons, some of which Rogoff highlights. But I am not convinced that the US is completely immune either. They do have exceptionally strong demographics for a mature, developed country, so I can see why this wouldn't be on American economists' radar. And if it is not a relevant theme for American economists, can it be on anyone's radar? I do believe, however, that it is relevant for many countries and that the US may be indirectly impacted in a not-too-distant future. In particular, while I share Rogoff's optimism about European growth as a result of US isolationism, I am worried about European sovereign debt because of these deflationary dynamics. I am obviously bearish on Japan. If the US ever finds itself in such a demographic situation, my prediction is that they will turn to inheritance taxes - a significant reserve of wealth that they have barely tapped into so far.

The Exorbitant Privilege

One aspect that I highlighted in previous posts on business and economics, and that few people grasp, is the immense power the US wields through the dollar(3). Its currency is, de facto, an instrument of global regulation, and I found Ken Rogoff's commentary that sanctions spared the US a few wars to be quite smart. This is all possible because the US regulates downstream uses of the global trade currency and can issue sanctions to systemic financial institutions that do not enforce American laws. There are countless examples of the weaponization of the dollar, notably as leverage in negotiations on completely different topics. I once wrote about the story of Executive Life's junk bond portfolio and how Crédit Lyonnais had to settle for $700 million, the highest amount ever paid in such a context at the time. Paying that much was a no-brainer compared to the risk of losing access to American financial markets, and even more so, the ability to settle transactions in US dollars. Since then, the risk has only become greater for financial institutions, and there have been examples of settlements exceeding $10 billion.

This brings me to two other things that Ken Rogoff mentions:

- The European Central Bank Digital Currency (CBDC) could impact American influence because it would allow others to circumvent US financial infrastructure and therefore US influence. I have reservations about CBDCs but had never thought about them that way; I found this sufficiently interesting to add to a talk I am giving next week on Decentralized Finance.

- Another Crédit Lyonnais story linked to the wave of rapid deregulation of the financial sector. Pushed by the US in the first half of the 1980s and implemented globally by the mid-1980s, it directly led to financial crises in countries that had historically controlled their financial sector heavily. Rogoff mentions Japan, but I have seen it (and personally studied it extensively) in France. What happened is that the central power (the "technocrats") relinquished control before lawmakers could implement their own, which created an incredible opportunity to build up hidden leverage. Hidden leverage means that risk is concealed in complex structures, and intermediaries can extract value stemming from the mispricing of that risk by end-users(4). In France, as in Japan, the playbook was applied in the second half of the 1980s. It was obviously more visible in Japan from an external standpoint, but Crédit Lyonnais was the third-largest bank in the world at the beginning of the 1990s. Ironically, Crédit Lyonnais was one of the few French banks that had not been privatized (but was managed like its private competitors, probably more aggressively). When it failed, it was a wake-up call for the rest of the sector, which was in very bad shape. The naming-and-shaming that ensued brought order to an ecosystem that could have imploded in a much more spectacular manner. This episode was very much the equivalent of financial repression.

I didn't fully agree that the handling of the Euro Crisis had no consequences for Europe; Europe started to trail the US economy from that period on, as Dwarkesh pointed out. I think it is important to understand the links between the private economy and public financing. Monetary policies have long-lasting implications for the real economy. Rogoff touched on this but, in my opinion, didn't push the reasoning far enough. For example, I am not convinced it makes sense to say that China has a massive public debt problem at the local level, while private sector indebtedness in the US is going through the roof, but that's not a problem. They are not fundamentally different problems and will have to be solved with the same tools: inflation, financial repression, austerity, defaults.

Miscellaneous Notes

- On a personal note, I really loved the mention of my hometown, Rouen, France. I have to say that when I listened to the podcast on my home trainer, I thought Rogoff was trying to say Orléans.

- I like the framing of Canada and Australia as structurally more conservative countries from a fiscal perspective because their income streams depend on volatile commodities. I also share Rogoff's pessimism about the UK.

- I found the reference to Treasury Inflation-Protected Securities (TIPS) to illustrate ZIRP (Zero Interest-Rate Policy) to be super insightful. Not sure why I never thought about that, but here is the chart.